|

Table of Contents CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1Introduction This chapter serves as ‘a foundation chapter’, as it covers the key aspects (research problem, objectives and questions) from which the other chapters proceed. The chapter starts with an overview of the education system in Tanzania so as to establish the position of the study. That is, to put it clear as to what type of school committee the study was confined. After the overview, it proceeds to highlighting the Background to the study, Statement of the problem, Research objectives, and Research questions. The chapter The Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org 1.2 Background to the study 1.2.1 An overview to the education system in Tanzania The pre-primary education is provided for children aged five to six years. Usually, there is no formal examination which promotes pre-primary children to primary schools. Instead, pre-primary education is formalised and integrated into the formal primary school system. Primary schooling in Tanzania is universal and compulsory for all children from the age of seven. The primary school cycle begins with standard one (STD I) on entry, and ends with standard seven (STD VII) in the final year. At the end of standard seven, pupils sit for the National Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE). This examination acts as a selection examination for entry to secondary education (Form One). A Primary School Leaving Certificate (PSLC) is awarded to all children who complete standard seven (United Republic of Tanzania, 2006).

1.2.2 Management of primary education in Tanzania In 2000, the government of Tanzania undertook an overall Education Sector Review Programme, with the major focus centred on primary education. This was followed by the launching of the Primary Education Development Programme (PEDP) in 2002, aimed at improving education quality, expanding school access, and increasing school completion at the primary level. This involved measures to increase resource availability and improve resource allocation and utilization; to improve educational inputs; and to strengthen institutional arrangements for effective primary education delivery by particularly empowering the stakeholders at the grassroots (United Republic of Tanzania, 2001). However, while there is high consensus on the fact that citizen empowerment in the management of social services in particular, education has a significant potential for enhancing accountability and local participation in public sector service delivery, it is not quite clear about the degree to which it contributes to improved service delivery or performance at the grassroots level for that matter.

1.4 Statement of problem 1.5 Objectives of the study To examine the procedural requirements for members’ selection, composition and service tenure of the school committees; What procedures are followed in the actual practice of selecting the school committee members? Is there any stipulation in regard to composition and tenure of service of school committee members? How do all these affect the committees’ performance? What is the level of commitment of individual members to work as representatives of the community in decision making at the school? Are they satisfied? What motivates them to become members of the school committee? How does this influence their performance? What is the role of school committees when it comes to decision making and implementation at the local level? Are they given autonomy? What are the boundaries of this autonomy? How does it affect the performance of the school committees?

The rationale of the study rests on the fact that the Education sector in Tanzania has undergone fundamental transformations as a result of the major administrative, economic and political reforms that have taken place in the country in the last decade. not much has been done to#p#分页标题#e# a means to expose some strengths and weaknesses of school management committees as the means to empower citizens at the local level in the management of education and hence, providing some bases of argument for or against the effectiveness of the school management committees in the country; 1.8 Limitations of the study 1.9 Delimitation/scope of the study CHAPTER TWO: 2.1Introduction This chapter provides the theoretical framework and review relevant literature to the study which sought to examine the empowerment of the primary school governance structures (the school committees) and how this influences their performance at the local level in Tanzania. The chapter ultimately depicts the position of the study within the wide context of existing literature. Three main parts are highlighted in the chapter namely, Review of related literature, Citizen Empowerment in the Tanzanian context and Operationalisation of empowerment. In the introductory part, the main concern of the essay and theoretical framework of the study are highlighted. Literature has been reviewed in the broad and narrow perspectives of empowerment and participation.#p#分页标题#e# 2.2 Theoretical framework of the study 2.3 Other Theoretical perspectives (competing theories)

2.3.3The attitude theory An attitude can be explained as “a predisposition to behave in a certain way” (Chapman et.al, 2002), often operationalised it as the likelihood that people’s expression of positive or negative regard toward an object, issue or event predicts the direction and intensity of their consequent behaviour towards it. The prominence of the attitude of a particular person towards an issue is largely a function of the extent that the individual has thought about the issue. Therefore, in attitude measurement, when people are asked about their attitude toward an issue with which they have little familiarity, their responses tend to lack dimensionality and vice versa. In this theoretical perspective, local community members’ /school committee members’ attitudes towards their schools are said to be a factor in determining the extent and nature of their participation in the education decisions that rest at the local/ school level and in explaining their performance in the implementation of the school development projects.

2.4 Empowerment theory: A review of literature

In the perspective of work organizations, the concept of empowerment has also been associated with popular management movements of the times such as HRM[ Human Resource Management] and TQM[ Total Quality Management] of the 1980s as an attempt to address the chronic problems of Taylorism and bureaucracy which dominated the workplaces (Wilkinson, 1998). Although the scientific management theory by F.W. Taylor[ Taylor is respected as ‘the father of scientific management’. Under his management system, factories are managed through scientific methods rather than by use of the empirical ‘rule of thumb’ so widely prevalent in the days of the late nineteenth century when F. W. Taylor devised his system and published ‘Scientific Management’ in 1911. ] was very successful in terms of increasing productivity,指导留学作业提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 workers’ dissatisfaction was immense as reflected in high labour turnover, absenteeism and conflict. It is the work of Elton Mayo[ Elton Mayo conducted the popular Hawthorne experiments (1927 -1932) where he found that work satisfaction is enhanced, to a large extent, by the informal social relationships between workers in a group and upon the social relationships between workers and their bosses. The effects of the group should never be underestimated.#p#分页标题#e# From the analysis above, it can be concluded that the concept of empowerment is a result of contributions from various disciplines, making it a multidisciplinary concept that no single discipline can claim to ‘own’ it.

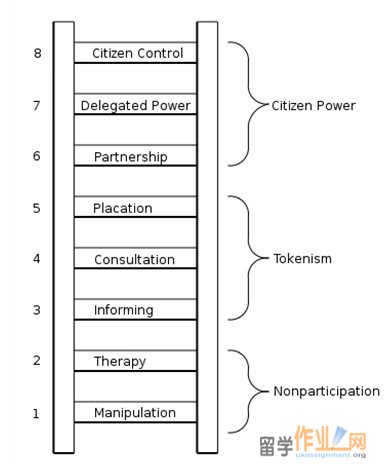

The World Bank defines empowerment as the expansion of assets and capabilities of poor people to participate in, negotiate with, influence, control, and hold accountable the institutions that affect their lives (World Bank, 2002). This is an institutional approach to empowerment of men and women through removal of formal and informal institutional barriers that prevent them from taking action to improve their wellbeing both individually and collectively. It is a transformational process through which individuals and groups are enabled to take greater control of their lives and the environment. Empowerment envisages enabling individuals to pursue their goals successfully through positive integration at the micro (individual) and macro (community) levels. Empowerment is not a one-time event. Rather, it is a continuous process that happens over time. It has also more intrinsic than extrinsic value; though its instrumental values cannot be taken for granted (Rappaport, 1981). In other words, one should not wait for others to empower them. Empowerment comes from oneself and others only support the person’s empowerment. Rappaport thus views empowerment as a construct that links individual strengths and competencies, natural helping systems, and proactive behaviours to social policy and change. According to Kabeer (2001: 19), “empowerment refers to the expansion of people’s ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was denied to them”. In Kabeer’s framework, empowerment is analysed under three major dimensions that define the individual’s capacity to exercise strategic life choices namely; access to resources, agency and outcomes. UNDP (2004) defines empowerment as “the process of transforming existing power relations and of gaining greater control over the sources of power” (UNDP[ United Nations Development Programme], 2004:12). This definition takes the human development approach, which views empowerment as an attempt to create an environment where people can develop their full potentials, making them creative in improving their lives according to their needs and interests and enabling them to participate actively in the development process.#p#分页标题#e# Other writers explore empowerment at different levels: personal (psychological), implying a sense of self confidence and capacity; relational, implying ability to negotiate and influence relationship and decisions; and collective (Rowlands, 1997), which implies collective action to improve the quality of life in the community and to the connections among community organizations. However, organizational and community empowerment are not simply a “collection of empowered本站提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 individuals” (Perkins and Zimmerman, 1995: 571).  Arnstein (1969) constructed a model (the ladder of citizen participation) to explain the concept of participation. Her ladder of citizen participation was divided into eight rungs, ranging from non-participation (therapy and manipulation) to tokenism (informing, consultation, and placation) to citizen power (partnership, delegated power, and citizen control) as depicted in figure1. According to Arntein’s conception, Participation is not an absolute. Rather, it occurs on a continuum from lesser to greater participation. In this view, different scales of community participation exist. Through this ladder of citizen participation, empowerment can be explained as the highest form of citizen participation (rugs 6, 7, and 8). When potential beneficiaries can also make key development decisions, participation becomes a self-initiated action and meaningful. This is what Arnstein refers to as ‘having the real power needed to affect the outcome of the process’ (Arnstein, 1969: 216). Participation encompasses both weak and strong forms of citizens’ power with regard to decision making/control over their development. As illustrated in the typology of eight levels of citizen participation, each rung in the ladder denotes the degree of citizens’ power in decision making. With the first two rungs which Arnstein calls manipulation and therapy, there is no authentic participation but rather, the power holders use the participation theory to legitimate their domination over the citizens’ power over decision making. This is what Bray terms as “the empty ritual of participation” (Bray, 1999:10). Basically, the two bottom rungs constitute the weakest form of citizen participation, which in practical terms may be regarded as ‘non-participation’. Under the ‘illusion’ of participation, citizens can be manipulated to form advisory committees or boards to serve their interests, while in practice, they perform ‘a mere rubber stamp role’ as they cannot influence the decision making process. Citizen participation of this type (in my opinion) is meant by the power holders to enhance public relations and to impress the international community especially, the donors. #p#分页标题#e# Rungs 3, 4 and 5 (Informing, Consultation and Placation respectively) constitute the second level of citizen power which Arnstein calls "tokenism". At this level citizens have the opportunity to hear and to have a voice by being informed and consulted, but they lack the power to assure that their views will be taken seriously by the power holders. With this form of participation, there is no follow-through, no power, and hence no possibility of changing the status quo. Although rung 5 (Placation) is sometimes considered a more genuine approach to participation, yet citizens are not conferred full power to decide. In this view therefore, it can simply be considered as “a higher level tokenism”. This form of participation has been seen in the School Governing Bodies (SGBs) in South Africa, which seem to be there simply as the means to contain parental discontent and mobilize additional resources for running the schools. Parents’ participation in particular, depends significantly on what they are "allowed" to do by principals (Lewis and Naidoo, 2004:106), and it is restricted to ‘token involvement’ in fund-raising and other support activities. The three upper rungs of the ladder (rugs 6, 7, 8) are levels of citizen power with increasing degrees of decision making. Citizens can enter into a Partnership that enables them to negotiate and engage in power sharing with traditional power holders. The two topmost rungs (7 and 8) involve Delegated Power and Citizen Control respectively. At these levels, citizens have strong power to make decisions. Arnstein’s ladder analogy was applied and further developed by various authors. Weidemann and Femers (1993) used it to classify the public rights and analysis of decisions needed for hazardous waste management. According to their analysis, public participation increases with the level of access to the information as well as the rights that citizens have in the decision making process. This is what empowerment consists in. The conception of empowerment by the IFAD[ International Fund for Agricultural Development] encompasses both access to resources and the capacity to participate in decisions that affect the least privileged (Moore, 1995) The critique to the eight-rung ladder designed by Arnstein is that it is an over- simplification of reality. Taking the concept of participation as a linear process of eight levels that can be presented in a ladder metaphor is unrealistic. There is no clear-cut of where exactly each level in the ladder begins and end because social science phenomena are not the same as those of the natural science. However, like any other model, it helps to facilitate understanding of the fact that there are different forms of citizen participation. Knowing these gradations makes it possible to distinguish between meaningful/genuine citizen participation and non-participation. 2.6 Operational sing empowerment

Taking into consideration that empowerment is a multileveled, multifaceted and context-based concept (Schulz et. al, 1995); can we really have a common understanding about empowerment? In other words, is there a model/framework that can be claimed to be a panacea to all contexts? Certainly, it is difficult to have one. Let us take an example of a situation where we want to empower poor women to enable them to own and dispose land, and another situation where we want to empower local communities to take charge of managing their local primary school.#p#分页标题#e# By looking at these two cases, we learn that there are so many disparities in their nature and context that they necessitate the use of different strategies. The first case is meant for poor women as the main target while the second one is meant for the entire community: men, women, children, rich, poor etc. While the first case is more in the economic context (land ownership and disposal), the second is more of the social- political context (ownership sector ownership, governance and accountability). The nature of the first case might be embedded with some cultural barriers (values and norms) that have been internalized as those inhibiting women to own land and other properties, while the second might have comparatively fewer complications owing to its being a service provision endeavour, meant for the children of both parents (men and women). It is from the variations among the contexts (social, political, institutional/economic and cultural) that complicates the intervention strategies. Yet in practice, the empowerment strategies are not formulated in a static environment. The environment changes with time, and so should the strategies be to suit a given context. Now the question remains: ‘what are the fundamental elements of empowerment that will at most cut across all contexts and remain relatively stable (consistent) in the turbulent social, political and institutional environments’? The answer to this question will then form the basis for our framework. Various elements have been identified by various scholars. However the suitability of a particular framework本站提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 of elements will depend upon the frequency at which they feature in successful empowerment efforts (World Bank, 2002).

2.7The World Bank’s model

Although it is not possible to have a single model for empowerment, experience shows that certain elements are almost always present in successful empowerment efforts regardless to the differences in the contexts of empowerment interventions. It is from this view; the World Bank (2002) attempted to identify some key elements that at most tend to feature in most of the successful projects. The bank comes up with four fundamental elements of empowerment that must underlie institutional reform. The elements include: Access to information, Inclusion / participation, Accountability and Local organizational capacity. 2.7.1Access to information

Information is power. Well informed citizens are better equipped to take advantage of opportunities, access services, exercise their rights, negotiate effectively, and hold state and non-state actors accountable. Releasing information about the performance of institutions, future plans and many other issues of interest enhances transparency in the government, public service, and the private sector. Regulations about rights to information and freedom of the press promote informed citizen action. In this view they should be easily available by every citizen. Unrestricted two-way information flow from government to citizens, and from citizens to government is critical to responsible, responsive and accountable governance. The basic assumption here is that access to information promote stakeholders’ knowledge, competences and initiatives; making them more effective in their performance. The more the information they have, the higher is their self-confidence and initiative to make decisions and the higher is their performance.#p#分页标题#e# Citizen participation should be meaningful. A meaningful participation is the one that results in change of the status quo. Experience shows that poor people do not participate in activities when they know their participation will make no difference to products being offered or decisions made because there are no mechanisms for holding providers accountable. An empowering approach to participation should therefore treat poor people as co-producers, with authority and control over decisions and resources devolved to the lowest level. Depending on the situation, participation may be direct (by individual citizens), representational (through representatives from membership-based groups and associations or committees. 2.7.2 Inclusion/ participation

Opportunities for all citizens to participate in decision-making are critical to ensure that the use of limited public resources builds on local knowledge and priorities and brings about commitment to change. In order to ensure inclusion and informed participation, it is important to ensure that the institutional rules create room for people to debate on various issues, participate in local and national priority-setting and in the delivery of basic services. Citizen participation should be meaningful. A meaningful participation is the one that results in change of the status quo. Experience shows that citizens do not participate fully in activities that they know their participation will make no difference to the existing situations. An empowering approach to participation should therefore promote partnership between the citizens and the government/institutions. Authority, control over decisions and resources should be devolved to the lowest level. Depending on the situation, participation may be direct by individual citizens such as in voting; and representational (by selecting representatives from membership-based groups and associations) such as the primary school committees in Tanzania (Fundi, 2002), the School Governing Boards (SGBs) in South Africa (Lewis and Naidoo, 2004) and the Parent Teacher Associations (PTAs) and School Management Committees in Ghana (Fusheini, 2005). The basic assumption here is that the more authentic is the participation/inclusion, the more likely is the success of a particular development intervention.

2.7.3Accountability Accountability encompasses the obligations of political authorities, parties and representatives to explain their intentions and conduct to their constituencies and to voters at large and the responsibility of government agencies to fulfil their administrative and social commitments to citizens by presenting transparent periodic reports of their work for public scrutiny and discussion. Citizen action can strengthen political and administrative accountability mechanisms and put up demands for better governance and transparency. A variety of mechanisms exist to ensure greater accountability to citizens for public actions and outcomes. Access to information by citizens builds pressure for improved governance and accountability in areas such as setting priorities for national expenditure, enhancing access to quality education, ensuring that roads once financed actually get built, or seeing to it that medicines are actually delivered and available in clinics. Access to laws and impartial justice is also critical to protect the rights of poor people and pro-poor coalitions and to enable them demand accountability, whether from their governments or from private sector institutions. Citizen action can reinforce political and administrative accountability mechanisms and build pressurise on improved governance and transparency. In Tanzania, it was found that local participation in school affairs particularly financing and management through the Community Education Fund (CEF) inculcated local accountability of schools to the local communities (United Republic of Tanzania, 2003).#p#分页标题#e# 2.7.4 Local organizational capacity Local organizational capacity refers to the ability of people to work together, organize and mobilize resources to solve problems of common interest. Often outside the reach of formal systems, poor people turn to each other for support and strength to solve their everyday problems. Poor people's organizations are often informal, as in the case of a group of women who lend each other money or rice. They may also be formal, with or without legal registration, as in the case of farmers' groups or neighbourhood groups. The assumption here is that organized communities are more likely to have their voices heard and their demands met than unorganized communities. It is only when groups connect with each other across communities and form networks or associations (federations) that they begin to influence government decision-making and gain collective bargaining power. 2.8 The Resources- Agency- Outcomes model

Kabeer[ Researcher and women empowerment analyst from the Institute of Development Studies in Sussex, United Kingdom] views empowerment from the perspective of ‘power’. She argues that one of the approaches through which power can be conceptualized is in terms of “the ability to make choices” (Kabeer, 2001:18). Analogously, disempowerment can be conceptualized in terms of ‘choice denial’. In this view, denying people the opportunity to make their own choices amounts to disempowerment. Empowerment is thus an attempt to enhance poor people’s freedom of choice and action by removing formal and informal institutional barriers[ Formal institutions include: state, markets, civil society and international agencies whereas the informal ones include: norms of social exclusion, exploitative relations and corruption.] that inhibit them from taking action towards improving their wellbeing both本站提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 individually and collectively (World Bank, 2002). By carefully examining the logic of Kabeer’s argument, I consider empowerment and disempowerment as coexisting constructs, and that whenever there are empowerment efforts, there must have been a perceived state of disempowerment that necessitated launching of the empowerment interventions. With regard to enhancing one’s freedom of choice, there must be options. That is, their ability to have chosen otherwise. It is from this fact poverty is often associated with disempowerment because in such a situation, one may have no alternatives for making choice. This is so because in a situation where people have insufficient means to meet their fundamental needs, their ability to exercise meaningful choice is automatically ruled out. It is also important to note that choices are not equally relevant to the definition of power. Some choices are more important than others. These are the ones referred to as “strategic life choices[Strategic choices are critical for the people to live the life they want. They include for example, choice of livelihood, where to live, whether to marry, who to marry, whether to have children, how many children to have, freedom of movement, and choice of friends... They are also referred to as ‘the first order choices.’ ]” which help to frame other, “less consequential choices”[ Also called ‘second-order choices’] which may be important for the quality of one’s life but do not constitute its defining parameters (Kabeer,2001:19). The model takes into account the role of three inter-related dimensions which facilitate choice: Resources, Agency and Achievements.#p#分页标题#e#

2.8.1 Resources

‘Resources’ constitute the first dimension of power in this model. Resources in this respect are conceptualised in a broader perspective, encompassing the conventional economic resources such as land, equipment, finance and working capital as well as human/social dimensions nourishes one’s ability to exercise choice (Kabeer, 2001). ‘The human resources’ are within the individual, and they include their individual knowledge, skills, creativity, imagination and the like. Human resources do not end up there. They also constitute claims, commitments and expectations inherent in the relationships, networks and contacts that take place in the day to day operations and long term activities in various areas of life. Having the resources is one thing. The question now comes: ‘How the resources are distributed to the people’? This brings in the institutional arrangements and processes to govern resource distribution. Access to resources is governed by rules, norms and practices that are embedded in various institutional domains (family norms, employer- employee relationships, patron- client relationships, informal wage agreements and public sector entitlements, just to mention a few. It is through the rules and norms some actors (household heads, heads of tribes, heads of organizations and others) are given power over others in shaping the modalities of allocation and exchange within particular institutional contexts in respect of the positions they hold. The way through which people gain access to resources is crucial. Lack of access to resources is equally the same as lack of resources themselves when it comes to analysis of empowerment. Empowerment in this respect means improvement of access to and acquisition of resources. The way through which people gain access to resources is crucial. Lack of access to resources is equally the same as lack of resources themselves when it comes to analysis of empowerment. Empowerment in this respect means improvement of access to and acquisition of resources.

2.8.2 Agency This is the ability to define one’s goals and pursue them. It includes observable (activities) and unobservable actions like the meaning, motivation, motives of individuals in their activities. Agency is also termed as ‘power within the individual.’ Its measurement can be done through ‘individual decision making’. It encompasses a wide range of purposive actions such as bargaining, negotiation, deception, manipulation and some more intangible cognitive dimensions such as reflection and analysis. Agency has both positive and negative meanings in relation to power (Sen, 1999). In the positive connotation, it takes the form of ‘power to’. This is the people’s capacity to define their life choices and pursue their own goals even in the presence of external opposition. The negative meaning of power implies ‘power over’, i.e. the ability of an actor or group of actors to over-ride the agency of others. This can be through violence, coercion and threat. There are instances where power can also operate in the absence explicit agency where the norms governing social behaviour tend to ensure reproduction of certain outcomes without any apparent exercise of agency (Lukes, 1974). #p#分页标题#e# 2.8.3 Achievements The combination of resources and agency results into capabilities, which imply the potential that people have for living the lives they wish, and of achieving valued ways of ‘being and doing’ which according to Sen (1990, 1999.a) imply achievements realized by different individuals. Kabeer’s third dimension of power is constituted from the ‘achievements’ or failures as the case may be, though she cautions that there are some cases where failures to achieve valued ways of ‘being and doing’ can be a result of laziness, incompetence or other individual-specific reasons, so the issue of power becomes irrelevant. CHAPTER 3: DECENTRALIZATION AS A STRATEGY OF ENHANCING CITIZEN POWER

3.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses decentralization as a strategy of citizen empowerment. Decentralization has been discussed both in theory and practice, linking it to the concept of citizen empowerment. The chapter presents a review of literature on public sector decentralisation in general, comparing different perspectives. The chapter narrows down to discussing the decentralisation policy in Tanzania and in particular, the educational decentralisation policy framework. The chapter captures some important trends in the development of the primary education management in the country since her independence in 1961. The relevance of reviewing decentralisation theory and practice to this study rests on the fact that citizen empowerment depends on the relationship between the state institutions. That is the decision making machinery from the centre to the periphery. Decentralisation was opted for by many countries of the world (Tanzania being one of them) as a means本站提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 through which citizen power can be enhanced at the local level. In a nutshell, the essence of decentralisation rests on promotion of democracy, efficiency, accountability and responsiveness to local needs. Therefore the concept of decentralisation has been utilised in this study because of its inseparability from the concept of citizen empowerment. The latter has been used as a means to realise the former. Decentralisation focuses on community participation, collaboration, equitable distribution of resources and local decision making (autonomy) which are key variables of citizen empowerment. 3.2 Different conceptual orientations

Decentralisation has been viewed differently by various people. While most of the views are unanimous on the idea that decentralisation concerns the ‘shifting of decision making authority and power from a central point (such as the central government) to its local units (local government), there are some differences with regard to the scope and specificity (Dyer and Rose, 2005). For instance, while some definitions focus on the partial transfer of authority and power from the centre to the periphery (deconcentration and delegation), others suggest total shifting of authority and power from the central point to its respective local units (devolution).#p#分页标题#e# Conversely, some definitions of decentralization are specific in terms of the functional areas that are transferred to the local levels whereas others do not. For example, Rondinelli and Cheema (1983) specify in their definition that functions like planning, decision making and administrative authority need to be transferred from the central to local authorities. According to Brinkerhoff and Azfar (2006: 2), “Decentralization deals with the allocation between center and periphery of power, authority, and responsibility for political, fiscal, and administrative systems”. The authors are more specific here with regard to what is decentralized and the scope of functions. In contrast, McGinn and Welsh (1999) consider decentralisation generally as the transfer of authority from central government to provincial, district and school levels. In the same way, Geo-jaja (2004) describes the concept of decentralisation as “a process of re-assigning responsibility and corresponding decision making authority for specific functions from higher to lower levels of government”(Geo-jaja, 2004: 309). From these points of view, it can be said that there are differences in meanings and motives of decentralisation.

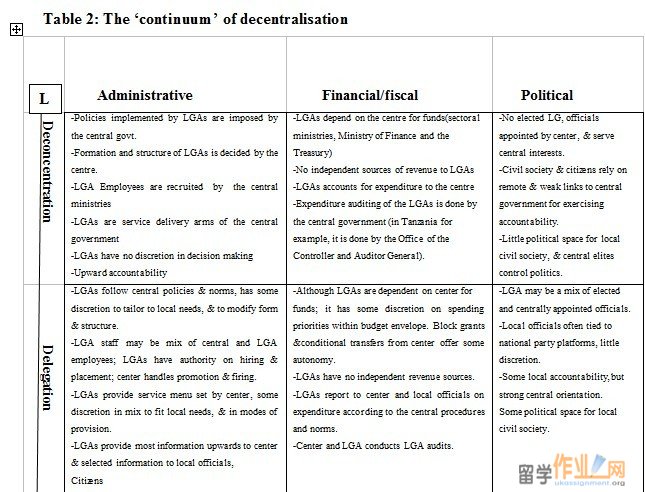

To sum up what has been grasped from the various viewpoints and extend a little bit the scope of argument, Decentralization can be described as the transfer of decision making authority and responsibility from central to lower levels of government or private institutions. The transfer of authority and responsibility may encompass such aspects as planning, resource distribution, administrative and management tasks (Dyer and Rose, 2005; Abu-Duhou, 1999). Local authorities may be provinces (for federal states like that of the United States and Nigeria), and Regions (for unitary state like those of most African countries like Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda). Decentralisation also involves transfer of authority and responsibility from the central government to the local government authorities (LGAs) and institutions (city, municipal, town and district councils, villages and schools) depending on the context of the country in question. Most of the popular definitions of decentralization differentiate alternative levels of decentralisation along a continuum. At one end of, the center maintains powerful control with limited power and discretion at lower levels (deconcentration) to more and more diminishing central control with increasing local discretion at the other (devolution). The devolutionary end of the continuum is associated with more democratic governance, expanded discretionary room to make decisions at the local level and a shift in accountability from upward to downward orientation (Brinkerhoff and Azfar, 2006).

3.3 Public sector decentralisation

My concern in this part is to examine decentralisation of the public sector because it has always been the most important pillar in supporting national development, not only in the developing countries but also in the developed ones. Public service provision in most of the countries is at large provided by the state. Even where these services are provided by private bodies, non-governmental organisations and/or civil societies, the state remains the principal regulatory body. This part of the chapter therefore attempts to analyse decentralisation in the public sector, focusing on the main types, forms and features, implicating them to citizen power and control at the local levels. Along this line of argument, decentralisation within the public sector can in essence be discussed under three main types namely; political, fiscal and administrative decentralisation.#p#分页标题#e# Political decentralisation can be explained as the transfer of political power and decision making authority to sub-national levels such as district councils, elected village councils, district councils and state level bodies. Where such transfer is made to a local level of public authority that is autonomous and fully independent from the decentralising authority, the process is referred to as devolution.

Fiscal decentralisation on the other hand, involves some degree of resource reallocation to local government which would allow it to function properly and fund allocated service delivery responsibility. The arrangements for resource allocation are usually negotiated between local and central governments. Normally, the fiscal decentralisation policy would also address some revenue-related issues such as assignment of local taxes and revenue sharing through local taxation and user fees.

Administrative decentralisation encompasses transfer of decision‐making authority, resources and responsibilities for the delivery of selected public services from the central government to the lower levels of government, agencies, and field offices of central government line agencies. Administrative decentralisation may be implemented in three forms of power relations between the centre and the periphery. These are: deconcentration, delegation and devolution depending on the scope of functions that are decentralised and the degree of autonomy allowed at the local levels. This can be explained as a ‘continuum’ of decentralisation (table 2) as discussed under the subsequent sub-heading.

3.4 The ‘continuum’ of decentralisation

Decentralisation is broad. It may take different forms ranging from the lowest to the highest degrees of power shift from the centre to the periphery. The levels of power-shift that constitute the ‘continuum’ of decentralisation are: de-concentration, delegation and devolution (Brinkerhoff and Azfar, 2006). Deconcentration is the transfer of authority and responsibility from one level of the central government to another, with the local unit being accountable to the central government ministry or agency which has been decentralised (Olsen, 2007). It is a form of decentralisation which involves transfer of a narrow scope of administrative authority and responsibility to lower levels of the government institutions. This form of decentralisation does not give the periphery (local authorities) ultimate power to make decisions (Rondinelli and Cheema, 1983; Dyer and Rose, 2005). Decentralisation by deconcentration is often considered as ‘a controlled form of decentralisation’ and is used most frequently in unitary states (Olsen, 2007); where the concern rests on relocation of decision making authority and financial and management responsibilities among different levels of the central government. The process can take two different ways. The first option is that the central government can just shift responsibilities from its officials in the capital city to those working in the regions, provinces or districts. The second option is that the central government can create a strong field administration or local administrative capacity under the central/ministerial control. (Olsen, 2007). In Tanzania, the decentralisation policy of 1972 is a real example of decentralisation by deconcentration. With this form of decentralisation, the central authority retains the final decision making responsibility, while the operations are shifted to the local authorities. For instance, decentralisation of education by transferring the responsibility of supervision of primary and secondary schools to the LGAs[ Local Government Authorities] where City, Municipal and District councils become responsible for the management of schools under the directives from the centre. With this type of decentralisation, LGAs usually have low scope of autonomy.#p#分页标题#e#

Delegation on the other hand, involves redistribution of authority and responsibility to local units of government or agencies that are not always necessarily branches or local offices of the delegating authority, with most of accountability still vertically directed upwards towards the delegating central unit. It is the transfer managerial responsibility for specific functions to local units, LGAs or NGOs[ Non Governmental Organisations] that may not be under the control of the central government (Rondinelli and Cheema, 1983; Bray, 1987; Olsen, 2007). In this form of decentralistion, the centre remains accountable for the activities that have been delegated to the periphery.

Despite the fact that with delegation decision making powers are conferred to the lower units, they may be withdrawn at any time. It is at this point, no much difference is seen本站提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 between deconcentration and delegation. Although the power conferred to the local units through delegation may imply a higher degree of autonomy as compared to that of deconcentration in as far as decision making is concerned, the power is not ultimate as the power still rests with the central authorities which have chosen to ‘lend’ them to the local one (Bray,1987: 132). Thus, it can be argued that the two forms of decentralisation (deconcentration and delegation) above present the weak forms of power at the local levels.

Decentralisation by devolution (D-by-D) is the form of decentralisation whereby the states gives full decision making power and management authority to sub-national levels and allows decision making at local levels without asking for higher level’s approval. The scope of devolution may cover matters related to financial, staffing and administrative functions, where formal authority is transferred to the respective LGA units (Rondinelli and Cheema, 1983; Abu-Duhou, 1999; Bray, 1987; Dyer and Rose, 2005). With decentralisation by devolution (D-by-D), full autonomy is given to the LGAs, limiting the responsibility of the central government authorities to exercising indirect/supervisory control over them (Abu-Duhou, 1999: 25). Under the D-by-D government system, the justification of decentralisation rests on its effectiveness and efficiency in resource utilization as well as responsiveness to local needs.

As part of the devolved system, privatization means that the government gives up responsibility for certain functions and transfer them to certain private enterprises (Rondinelli and Cheema, 1983, Lauglo, 1995) for the purpose of enhancing better performance. In summary, the discussion of the three major perspectives of decentralisation indicates that the concept is broad. There can be different types of decentralisation depending on the degree of control exercised at the central level. It is on this ground that decentralisation is viewed as a ‘continuum’ of decision making power conferred by the central authorities to the authorities at the peripheries. The degree of decision making power conferred depends much on the intentions of the centre. For example, in a situation where the central government wishes to exercise control and achieve quick decision making, it may opt for a decentralisation by deconcentration or delegation.#p#分页标题#e#

3. 5 Decentralisation policy in Tanzania Tanzania like many countries of the world has embarked on decentralisation programmes in order to establish local governments which can deliver quality services to the people in a participative, effective and transparent way, and promote direct accountability of the local authorities to the people. However, despite these negative impacts noted, the benefits of decentralized governance are more explicit and cannot be taken for granted In as far as citizen empowerment is concerned; Tanzania considers decentralization as an appropriate approach to encourage local initiatives in the development process in the rural and urban areas, as it gives the people more power in decision making. By involving people at the local level in the planning, implementation, and evaluation process, a partnership is established between the government and the people in development interventions and hence, making the people feel as important stakeholders in the process. Since Independence, the government has adopted several decentralization measures geared towards promoting rural and urban development (Kabagire, 2006). These include: Launching of the Regional Development Fund (RDF) in 1967 which aimed at promoting self initiative in the development process.

Restructuring of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Development Planning in 1968/1969 whereby Regional Economic Secretaries were posted, to selected regions to coordinate the planning process. Ministerial reform in 1969 which came up with changes in the cooperatives and the creation of the Ministry of Regional Administration and Rural Development. Decentralization of government administration in July 1972 to give power to the people with regard to decision making concerning their development. A decentralized structure with clearly defined development responsibilities, coordination, and direction of the rural development work of all Ministries and Regions was established. A direct link between local organizations and the centre was established through the Regional Development Director (RDD). The decentralized structure consisted of the Regional Development Committees, the District Development councils and Ward Development Committee. Enactment of the Villages and Ujamaa Villages, Act of 1975 which further strengthened decentralization by establishing village councils that were charged with participatory development by the people at the local level, which was meant to realize the following four key objectives: First, to ensure that local development is effectively managed by organs that are closer to the people; second, to ensure full involvement of the people in the development process; third, to ensure that development is effectively planned and controlled; and fourth, to ensure that rural and urban development are centrally coordinated for efficiency and effectiveness.#p#分页标题#e# However, while central government administrative structures improved through this decentralization initiatives; actual participation by the rural and urban populace in the development process (citizen empowerment) was not realized significantly. The reason for the asymmetrical outcomes lies on the fact that this type of decentralization was more of de-concentration than devolution of power through local level democratic organs, where limited scope of power was conferred to the local authorities. This is why the government of Tanzania embarked on the policy of decentralization by devolution (D-by-D) in the 1990s. During this period, the Civil Service Reform Programme (CSRP) was launched, consisting of six components, including a Local Government Reform component. The reform of Local Government was aimed at decentralising government functions, responsibilities and resources to Local Government Authorities (LGAs) and strengthening the capacity of local authorities. Reform of the local government system was initiated in 1996 through a National Conference seeking to move “Towards a Shared Vision for Local Government in Tanzania.” (Mmari, 2005: 6). This vision was subsequently summarized in the Local Government Reform Agenda, and, in October 1998本站提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041, was endorsed by the Government in its Policy Paper on Local Government Reform (United Republic of Tanzania, 1998).

3.6 What can decentralisation contribute to the service delivery systems?

Looking at the positive side, Gurgur and Shah (2002) argue that decentralization minimises corruption that tends to crop up with bureaucratic and centralized authority. With decentralisation, there is accountability and transparency which in turn improves service delivery. In another study, King and Ozler (1998) observed that decentralized management of schools led to improvement in achievement scores in Nicaragua. Decentralization improves citizen’s access to social services and ensures that social services provided to citizens are responsive to the local contexts. This argument is confirmed by Faguet (2001), who found that decentralization in Bolivia helped improve consistency of public services with local preferences and quality and access of social services. This is also in concurrence with Dyer and Rose (2005) who claim that the quality of education can be improved by providing for decision making powers at the points of their implementation. In this way, it is possible to suit the local context in terms of expertise and experience. However the question remains to be ‘what form of decentralisation is adopted?’ in other words, how much powers are conferred to the local level in as far as decision making is concerned? Is it just symbolic or is intended to ensure meaningful citizen power? If the latter is true, there should be devolution of powers to the local levels and not merely deconcentration or delegation. Pointing out some key justifications for decentralisation of educational management by drawing on experiences of the developed countries, Caldwell (1990) cited in Govinda (1997) outlines six important arguments for the shift from central to peripheral control of education as follows:-#p#分页标题#e#

First, the perceived complexity of managing the modern education from one central point led to the governments’ acceptance of decentralised educational management systems. The essence of that shift lies on efficiency improvement. Second, the concern to ensure that each individual student has access to the particular as opposed to an aggregated mix of resources to cater for the needs and interests of that particular student. Third, some study findings in the developing countries with regard to school effectiveness and improvement have been insisting on decentralisation as a vehicle for success. Fourth, the fact that increased autonomy of the teachers and some bureaucrats at the local level increases ownership and commitment makes decentralisation an ideal strategy for educational management. Fifth, popular demand for more freedom and power of choice in terms of the schools they would prefer according to their perceived qualities by the general public; and sixth, the fact that the education sector should follow the reforms that were instituted in the other similar sectors which were earlier presumed to be solely the concern of the central government. Now with regard to how these are applicable to the developing world, much can be debated especially on the basis of the varying contexts of the developing and the developed countries. However, various studies have also revealed some negative impacts of decentralization policy. Using data from a cross-sectional study of industrial and developing countries, Estache and Sinha (1995) found that decentralization leads to increased spending on public infrastructure. In another study, Ravallion (1998) found that poorer provinces were less successful in favour of their poor areas in Argentina, and decentralization generated substantial inequality in public spending in poor areas of the country. Azfar and Livingston (2002) did not find any positive impacts of decentralization on efficiency and equity of local public service provision in Uganda; while West and Wong (1995) found that in rural China, decentralization resulted in lower level of public services in poorer regions. The Ugandan experience concurs with Sayed (1999); Soudied and Sayed (2005). Giving examples of South Africa and Namibia, the authors caution that decentralisation may promote inequalities or may lead to new forms of social exclusion in the settings where inequalities and social exclusion had been in existent before.

3.7 Educational decentralization in Tanzania

Educational decentralization in Tanzania aims to promote community participation in decision-making and cost sharing to ensure sustained effective provision of education and proper use and maintenance of school resources, and to reinforce planning and management capabilities at all levels of the school system. Educational decentralization in Tanzania is embedded in the general government decentralization framework (United Republic of Tanzania, 2007b.), called the Local Government Reform Program (LGRP). Various service provision responsibilities have been transferred to districts and Local Government Authorities (LGAs) through the Prime Minister’s Office-Regional Administration and Local Government (PMO-RALG). #p#分页标题#e# Primary education is the most important responsibility of local governments in Tanzania. Half of all their funds is spent on this activity (although most funds are provided by the central government), and two-thirds of all local government employees are teachers. Local government decision-making is vested in the district council. A majority of its members are directly elected at the ward level. At the lower level, the village council has much the same functions as the district council. At the school level the school committee (in which parents are represented) has the overall responsibility of overseeing the running of the school. 3.7.1Policy framework Education decentralisation in Tanzania is implemented under a framework of various interlinked policies. This section, therefore, is intended to provide the policy context under which education decentralisation takes place. 3.7.1.1 Tanzania DevelopmentThe Assignment is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org Vision 2025

Tanzania Development Vision 2025 was formulated in 1995, aiming at realising total elimination of poverty in the country by the year 2025. Tanzania’s Vision 2025 recognises education as a strategic agent for transformation of the citizens’ mindsets, and for the creation of a well educated nation adequately equipped with the knowledge needed to solve the development challenges which face the local communities and the nation as a whole. In this view, Vision 2025 stresses on restructuring and transforming education qualitatively, with a focus on promoting creativity and problem solving. Along the same line, Tanzania Development Vision 2025 devolves a greater role to the local actors to own and drive the process of their own development. The document puts it clear that the local people know their problems than any body from outside. In that view therefore, they can decide what they need to prioritise, what is possible to achieve and how it can effectively be achieved under the prevailing local conditions. 3.7.1.2 Education and Training Policy (1995)

The Education and Training Policy (ETP) was formulated in 1995 as a product of the liberalisation policy which started in Tanzania in 1986. The liberalisation policy came to effect in the country after the signing of an agreement with both International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) (Mrutu, 2007). As such, the thrust of the policy initiatives is privatisation, and changing of the role of state into facilitation as opposed to state ownership in the provision of services. The major aims of the Education and Training Policy include achieving increased enrolments, equitable access, quality improvements, expansion and optimum utilisation of facilities as well as operational efficiency of the entire system (Mhalila, 2007). It also aims at enhancing partnership in the delivery of education, the broadening of the financial base, the cost effectiveness of the education, and reformation education management structures through the devolution of authority to schools, local communities and Local Government Authorities (Mrutu, 2007).#p#分页标题#e#

3.7.1.3 Education Sector Development Programme (1996) The Education Sector Development Programme (ESDP) was developed in 1996. This followed the development of the Education and Training Policy that was formulated in 1995. ESDP is a sector wide approach that was initiated to facilitate achievement of the government’s long term human development and poverty eradication targets and to redress the problem of fragmented interventions under the project modality of development assistance. The essence of the sector wide approach is collaboration by the key stakeholders, using pooled human, financial and material resources for planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluation. This approach established new relations which promote partnership, co-ordination, and ownership amongst all groups of people with a vested interest in education (United Republic of Tanzania, 2001). It should be noted that the ESDP derives its objectives from the Education and Training Policy of 1995, as well as from the broader national development strategy of MKUKUTA and the long-term development plan of the country’s Vision 2025 (United Republic of Tanzania, 2001). The main education- related objectives include: comprehensive efforts to improve the quality of the education process, increase and improve access and equity for all children, the decentralisation of the management structures, the devolution of authority to local levels and broadening the financial base which supports the education system.

3.7.1.4 The Local Government Reform Programme (1998)

Reform of the local government system was initiated in 1996 seeking to move towards a Vision for Local Government in Tanzania. This vision was subsequently summarised in the Local Government Reform Agenda, and, in October 1998, was endorsed by the Government in its Policy Paper on Local Government Reform (Mmari, 2005). The programme implementation of the LGRP began on 1st January, 2000. The LGRP is a primary mechanism for the decentralisation and devolution of power to local levels, a main feature in the delivery of education at the primary level. The Local Government Reform Programme (LGLP) is a vehicle through which the government promotes and derives the decentralisation processes (Mmari, 2005). As such, LGRP is said to be an integral part of the wide public sector reforms. The Primary Education Development Plan (PEDP) for example, was set firmly within this decentralised framework and includes components that help to develop the capacity of personnel and structures at the local level, enabling the local level to participate in the comprehensive planning and delivery of high primary education services.

To conclude, we can say that the historical perspective presented herein and the current policy context have influence on the contemporary successes and challenges of decentralisation of primary education in Tanzania. Hence, knowledge of primary education trends and policy contexts will help in discussing the successes and challenges in the forth coming chapters.#p#分页标题#e#

3.8 Trends in the development of primary education in Tanzania

The Primary Education Sub-sector sector in Tanzania has undergone significant developments from 1961 when the then Tanganyika got her independence, all geared towards empowering the citizens. The trends can be traced along three major socio-economic development periods which the country has gone through namely, the period before Arusha Declaration(1961-1967); the Arusha Declaration era (1967-1986) and the period after Arusha Declaration /liberalization era (from 1986 to date). 3.8.1 The period before Arusha Declaration (1961-1967) Right after independence in 1961, the main concern of Tanzania mainland (the then Tanganyika) was to create an environment for socio-economic development. During the first Development Plan, the government identified ignorance as one of the major three hindrances of social and economic development in the country– others included disease and poverty (Nyerere, 1967). The then new government was determined to eradicate ignorance through investment in human capital, which with time would produce a healthy and well-educated population that is crucially needed for social and economic development. Towards this endeavour, Tanzania has undertaken a number of policy and development initiatives in the education sector with a focus to improve quality and access to school education. Investing on human capital was considered the main tenet towards creating a healthy and well educated population for social and economic development (Kamuzora, 2002). The new government enacted the Education Act of 1962 that repealed the colonial legislation (the Education Ordinance) that was in force since 1927 (Mamdani, 1996; United Republic of Tanzania, 1995). As a means to ownership by the local communities, the newThe Assignment is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org legislation intended to make Local Authorities and communities responsible for the construction of primary schools; provision of primary education; streamlined the curriculum; examination and financing of education (United Republic of Tanzania, 1995). 3.8.2 The Arusha Declaration era (1967-1986) It was during this period various attempts to reform education received a special impetus. Following the Arusha Declaration on 5th February 1967, President Nyerere launched the Education for Self-Reliance (ESR) policy to guide the planning and practice of education as a step towards putting the Arusha Declaration into effect, as the ESR policy was a programmatic follow-up of the objectives spelt in that Declaration. ESR policy envisaged embarking on curriculum reform so as to integrate the acquisition of practical life skills. This came up with the philosophy of linking classroom teaching with physical economic activities (self reliance activities) particularly agriculture. It also urged the linkage of education plans and practices with national socio-economic development and the world of work. The principles of Arusha Declaration emphasized on equal access to the scarce economic resources and social services such as primary education. In order to ensure adherence to these principles ,the government regulated and controlled all the production means such as land and other resources as well as social services such as education so that all Tanzanians regardless of their socio-economic status, ethnic origins, religious beliefs or gender (Galabawa, 2001). As a back-up to the Arusha declaration and the ESR policy aspirations, the Government of took several steps (Bana and Ngware, 2005). These involved among others, the enactment of the Education Acts of 1969 and 1978; the launching of decentralization programme of 1972 which in essence led to the abolition of the Local Government in the same year; and the start of Universal Primary Education (UPE) programme contained in the Musoma Resolution of 1974 (United Republic of Tanzania, 1982).#p#分页标题#e#

In November, 1974, the National Executive Committee of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) party met in Musoma in the northern part of Tanzania to review the country's progress in its policies of Socialism and Self-reliance. Some profound deficiencies were marked in the Implementation of the policy of Education for Self-reliance, especially at post secondary level (Biswalo, 1985). It was resolved at that time that from then on, formal education would basically end at the secondary school level. Secondary school graduates would serve one year in the National Service and thereafter, they would work for several years before they would be admitted to any post secondary institution. Post secondary institutions were, therefore, declared open for adult workers and peasants who satisfied the minimum entry qualifications for admission into higher education (Msekwa, 1975). This had implication to the primary education. Owing to the fact that only few candidates were selected to join the secondary school education, and because the secondary school level was meant to prepare the few selected graduates for work, the primary education (which was for all) was designed to prepare citizens for work both in the formal and informal sectors.

There is strong evidence that the steps taken in line with the Arusha Declaration accrued considerable success. The primary school enrolment rates rose to over 90 percent, with corresponding Net Enrolment Rates between 65 and 70 percent in the early 1980s (Davidson, 2004). However, this ‘success story’ was frustrated by the economic recession of the late 1970s as well as early 1980s, when Tanzania’s economy suffered seriously (Mmari, 2005). Much has been discussed about the causes of Tanzania’s and other third world countries’ problems during this period. Some writers argue that the key causes of the problems were external factors such as the oil price-shocks as well as deteriorating terms of trade (Galabawa, 2001), while others totally disagree with this line of argument. To them, the cause of this malaise is internal factors, especially weak and inappropriate policies and poor governance (Davidson, 2004). As a result of the crises, the 1980s witnessed increasing pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and donors in the development aid business, being put on Tanzania to accept the IMF Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) to address the crises.

In the mid 1980s, Tanzania started to implement the structural adjustment Programmes (SAPs) under the guidance and support of IMF and the World Bank (Msambichaka et. al, 1995). SAPs were intended to restore balance in the functioning of the economy as well as rationalizing resource utilization through domestic activities. It is widely believed that implementation of the SAPs has negatively affected social services provision in many of the developing countries. For example, a substantial reduction of public educational service in Africa occurred as a result of the SAPs because under these structural reforms, public expenditure on social services has been curtailed (Kiwara, 1994). The introduction of the cost sharing policy in the service provision sectors was embarked on to cut public spending on these services. The primary education fee was re- introduced in 1984, which excluded large segments of the population (the poor in particular) from gaining access to education (Ewald, 2002). This resulted in a considerable decline in the enrolment rate in the primary schools throughout the country. For the example, by 1993, gross enrolment in primary education had declined from 98 percent of the early1980s to 71 percent in 1988, and only gradually rose to 78 percent in 1997 (Lema, et. al 2004).#p#分页标题#e#

In addition, the state of physical infrastructure continuously deteriorated and schools faced serious shortage of major supplies such as text books, chalk and exercise books. Many pupils learned in overcrowded and poorly furnished classrooms.

3.8.3 The liberalization era (1986-to date)

The Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) of the 1980s had adverse outcomes to the primary education in Tanzania. In their study, Lema et al (2004) observed that in 1999, out of every 100 children of primary school age, 56 were enrolled in schools; of 56 enrolled in schools; only 38 completed primary school. Of the 38 who completed primary school, only 6 proceeded to secondary schools. Moreover, there were significant differences in school enrolment according to location reflectingThe Assignment is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org regional, district, ethnic and urban-rural differences (Mukandala and Peter, 2004). However, some recent studies have shown evidence of considerable improvement in the status of primary education in Tanzania since 2001 as a result of the Primary Education Development Plan (PEDP) (United Republic of Tanzania, 2004). The improvements could be attributed to the government’s abolition of the school fees and mandatory cash contributions from parents (Lema, et al, 2004). For instance, the Net Enrolment Rates have increased from 59 percent in 2000 to 91 percent in 2003, and Gross Enrolment Rates have increased from 78 percent to 108 percent during the same period. The actual enrolment grew by 50 percent up from 4.4 million in 2000 to 6.6 million in 2003 (Lema et al, 2004).

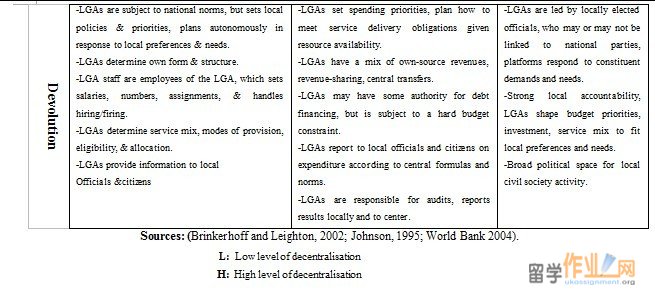

3.9 Analytical framework of the study

In the light of the reviewed literature, I developed a framework to guide my study. The basic assumption of the study is that: ‘Performance of the school committees depends on the extent to which they are empowered’. The study by Aedo (1998) shows the Chilean schools that have been conferred significant power to make decisions perform better than those under centralized control. In the same line, King and Ozler (2000) noted a positive effect of decentralization on parent participation in school decision-making in Nicaragua, while in on the other hand, Galiani, et. al .(2005) argue that decentralization of public schooling in Argentina in the early 1990’s helped to improve the quality of education in terms of standardized test scores. However, it seems that the studies focused more on the academic performance of the schools, which is not my concern in this study. Academic performance of students is a multi-dimensional construct, that many not be attributed to the functioning of school committees alone but some other factors such as availability and quality of teachers, suitability of the teaching-learning environment, motivation of teachers and pupils and government policies. In the proposed study, I intend to examine how the empowerment dimensions affect performance of the school committees by focusing on the administrative functions of the school committees such as resource mobilization, creation of infrastructure such as classrooms, planning and budgeting and finance. The reason behind this decision is that these responsibilities are specifically vested to the school committees at the local level under the educational decentralization system (United Republic of Tanzania, 2001); and therefore can easily be measured in a more direct way.#p#分页标题#e# 3.9.1 Dependent variable The dependent variable of the study is Performance of the school committees, and it was operationalised through the following indicators that have been established from the responsibilities of school committees as spelt in the PEDP document under the item “institutional responsibilities” (United Republic of Tanzania, 2001: 16). This will be operationalised in terms of Quality and timeliness of the school development plans and budget documents prepared; Implementation success that is, actual achievements against planned activities; financial reports prepared (timeliness and accuracy); and stakeholders’ perceptions on the performance of their school committees. 3.9.2 Independent variables From the assumption that ‘Performance of the school committees depends on the extent to which they are empowered’, the independent variables were the empowerment dimensions/indicators namely, access to information, inclusion/participation, capabilities /competences (knowledge and skills), Agency (willingness/motivation), autonomy and time (service tenure of the committees). Each variable will be measured as follows: 3.9.2.1 Access to information

This was operationalised by examining the extent to which school committee members has adequate information on their roles, the school, rules and regulations and policies and the number of meetings convened by school committees to inform parents and other stakeholders about the schools’ progress. The assumption here is that the higher the access to information by the school committees, the higher the performance (Behrman et. al, 2002). 3.9.2.2 Inclusion/participation

This was operationalised by finding out the extent of community members’ participation in electing the school committee members. The representativeness of the committee in terms of gender balance and inclusion of the marginalized groups was also examined. The assumption here is that participation makes the community members feel that the committee originate from themselves. This in turn, can enhance cooperation between the committee and the community. 3.9.2.3 Capabilities: knowledge and skill potentiality of committee members This variable was operationalised by assessing the educational qualifications, skills and competences possessed by individual school committee members; number of capacity building programs organized by the authorities responsible and attended by the school committee members; and future capacity building plans in place. The assumption here is that the higher the level of capabilities the higher the performance. As Behrman et.al (2002) argue, devolution of decision making to local and school levels make school management more accountable to the community, promote cost consciousness, efficiency and effectiveness. However, the authors are of the view that where capabilities are lacking on either sides (school management and the community, the outcome realisation is questionable.#p#分页标题#e# 3.9.2.4 Agency

This was operationalised by assessing the willingness /motivationThe Assignment is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org of the school committees to assume their roles and also the same was done to the local community members in terms of participation. Assumption: The higher the level of motivation the higher the performance. 3.9.2.5 Autonomy

This was measured in terms of the extent to which the school committees can autonomously make and implement decisions without external interference. The assumption here is that the higher the autonomy, the higher the performance. According to the study by Eskeland and Filmer (2002), there was evidence of positive correlation between performance and the autonomy of primary schools in Argentina, where more autonomous schools performed significantly higher than the less autonomous schools. The assumption under this variable is that that the higher the autonomy the higher the performance. 3.9.2.6 Time

This was operationalised by examining the tenure of service of the school committees. The assumption is that more tenure will give the committees an opportunity to perform better because of ‘strong teamwork’.

References Abu-Duhou (1999).School-based management. Paris: UNESCO/IIEP. Aedo, C. (1998). ‘Differences in schools and student performance’. In W.D. Savedoff (Ed.). Organization matters: Agency problems in health and education in Latin America (pp. 40-56). Washington, DC: IDB.