|

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

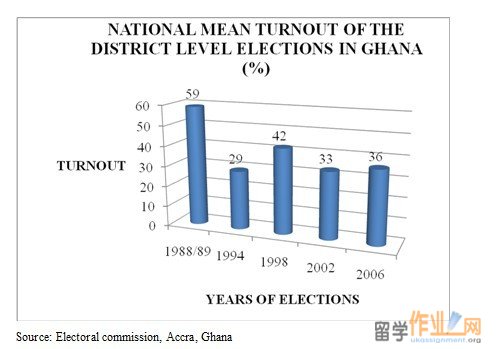

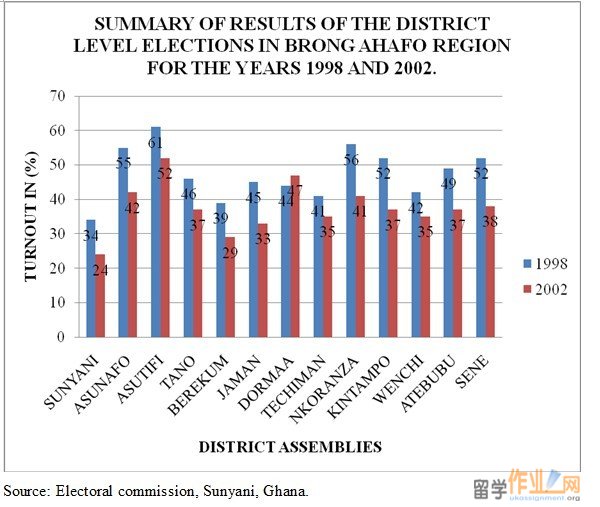

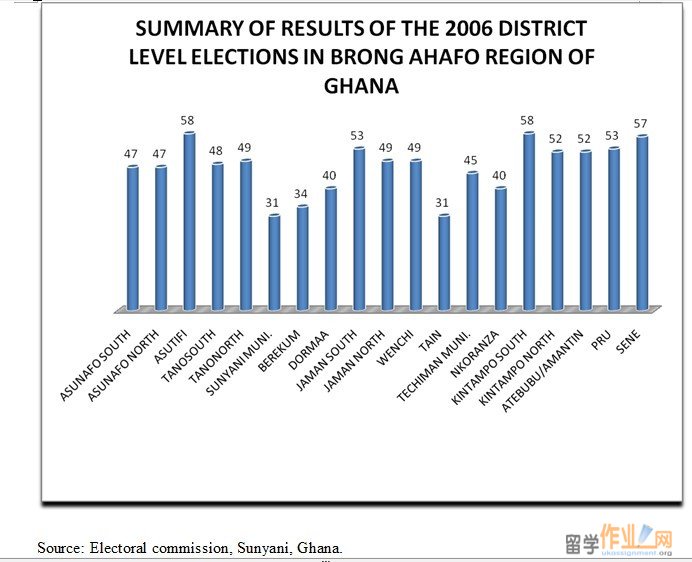

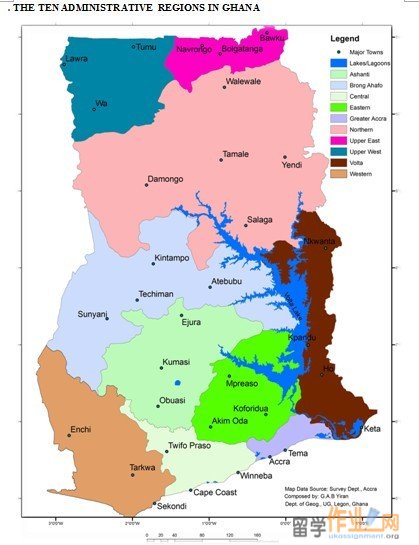

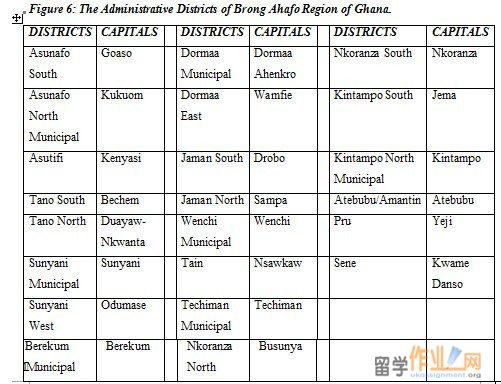

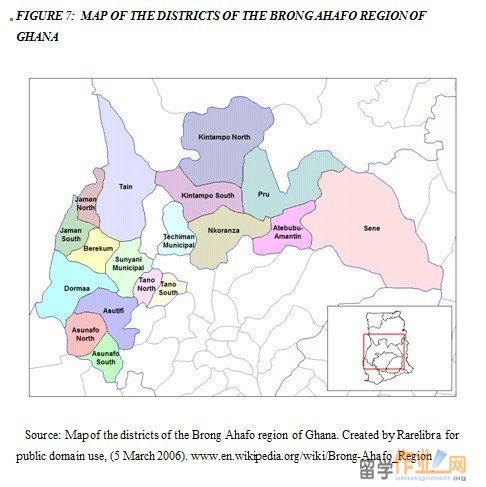

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY Ghana, formerly known as Gold Coast, is a country situated in West Africa and was the first place in sub-Saharan Africa where Europeans arrived to trade - first in gold and later in slaves. It was also the first black African nation south of the Sahara to achieve independence from a colonial power, Britain on 6th March, 1957. Ghana is a rectangular-shaped country bordered to the north by Burkina Faso, the east by Togo, the south by the Atlantic Ocean and the west by Côte d’Ivoire covering a land mass of 238,533 sq km (92,098 sq miles). Its current estimated population is 23.9 million (UN, 2008). The current 4th Republican Constitutional multi-party democracy was started in 1992 and since that time Ghana has been able to conduct five successful national elections. In African political and administrative history, decentralisation is not new. From the colonial period until the third quarter of the 20th century, decentralizations prevailed in the form of deconcentration almost without exemption. #p#分页标题#e# 1.2 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF DECENTRALIZATION IN GHANA The history of decentralization and local government in Ghana is traced back to the British colonial rule in the then Gold Coast, (Ghana) between 1878 and 1951 through the indirect rule. During this era the British colonial Administration governed indirectly through the existing chieftaincy institution, by constituting the chiefs and their elders in a particular district as the local authority, with powers “to establish treasuries, appoint staff and perform local government functions” (Nkrumah 2000: 55). As the first country in the sub-Saharan Africa to gain independence in 1957, successive governments in Ghana have searched for a vibrant local government system to support the country’s development. However, the most comprehensive and ambitious local government policy was initiated by the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) military regime in 1988,指导留学作业提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 the Local Government Law (PNDC law 207), through which the then 65 local authorities were reviewed and restructured into 110 district assemblies. In 1983, Rawlings’ PNDC government announced a policy of administrative decentralisation of central government ministries, together with the establishment of People’s Defence Committees (PDCs) in each town and village. The PDCs, made up of local PNDC activists as self-identified defenders of the ‘revolution’, effectively took over local government responsibilities, though often restricted to mobilising the implementation of local self-help projects (Nkrumah 2000: 58). The rationale for the local government reform as stated by the PNDC regime was to transfer functions, powers, means and competences from the central government to the local government, and to establish a forum at the local level where a team of development agents, representatives of the people and other agencies could discuss the development problems of the district and/or area and their underlying causative factors. On an ideological level decentralization was expected to support democratic participatory governance, improve service delivery and also lead to a rapid socio-economic development (Pinkney 1997, cited in Map Consult 2002: 35). Functionaries of the then PNDC government at different occasions justified the significance of the local government policy in Ghana. For example, in reacting to the criticism that the district assemblies were nothing but a move by the PNDC to consolidate its position, the chairman of the regime, Jerry John Rawlings stressed that the PNDC strategy and the rationale behind the decentralization policy was to take steps towards more formal political participation by every Ghanaian through the district-level elections which was to take place nationwide in that year. He said, “If we are to see a sturdy tree of democracy grow, we need to learn from the past and nurture very carefully and deliberately political institutions that will become the pillars upon which the people's power will be erected. A new sense of responsibility must be created in each workplace, each village, each district; we already see elements of this in the work of the Committee for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs), the 31st December Women's Movement, the June 4 Movement, Town and Village Development Committees, and other organizations through which the voice of the people is being heard”. In other words, a democratic local government was supposed to be the foundation for future national level democracy. Before the advent of the 1992 republican constitution in Ghana, the erstwhile PNDC government’s implementation strategy of the decentralization and local government policy encountered stiff opposition from strong democratic forces both within and outside Ghana as the regime’s legitimacy was quizzed. As a result of this legitimacy crisis of the regime, the PNDC government quickly finalized the implementation of the decentralization programme in 1987 to legitimize the regime through the District Assemblies (DAs) which were setup in order to “democratize state power and advance participatory democracy and collective decision making at the grassroots” (District Political Authority and Modalities for District Level Elections 1987:2). This paved way for the existing Local Authorities to be reviewed and restructured into District Assemblies and also new electoral rules such as common platform for all candidates vying for seats in the Assemblies to present their manifestoes to the public at no cost, right of the electorate to recall their Assembly-member before his/her tenure is due, the performance of Assembly’s business in both English and any other local language that was common in the locality, the abolition of property qualification right to stand for elections and non-partisan basis of the elections were among other things that were introduced into the new electoral process.#p#分页标题#e# At the end a voter registration exercise was undertaken and the first District Assembly elections were conducted in 1988 with an average national turnout of 58.9% was quite high by all standards especially when it was compared to the Local Council Elections in 1978, which recorded as low as 18% turnout (Oquaye, 1980:82). On that basis, when Ghana decided to change over from military dictatorship to constitutional liberal democracy in 1992, the first multiparty government- the National Democratic Congress (NDC) that came into power in 1993 decided to continue with the process of decentralisation. It therefore consolidated the aim of decentralisation within the new framework of liberal democratic constitution in spite of the fact that some essential democratic elements in the constitution remained compromised. Rationale for Decentralisation in Ghana The decentralisation programme had two main objectives: To create opportunity for the majority of Ghanaians who live in the rural areas – in villages and towns - to participate in decisions that directly affect their lives and increase their access to political authority Promote local development through the involvement of the indigenous people as a way of improving ownership and commitment to enhance implementation leading to improvement in the living conditions of the local people The underlying aim of the 1988 Local Government Law was “to promote popular participation and ownership of the machinery of government… by devolving power, competence and resource/means to the district level” (cited in Map Consult 2002: 35). The 1992 Constitution, which marked the transition to multiparty democracy at the national level, endorsed and consolidated the 1988 reforms, with few substantial changes. Therefore, the Constitution unambiguously stated that: “Local government and administration … shall … be decentralized” (Article 240[1]), and that “functions, powers, responsibilities and resources should be transferred from the Central Government to local government units” (Article 240[2]). The Constitution declared the DA as “the highest political authority in the district, [Article 241(3)], with the principles of participation in local government and downward accountability to the public accentuated by the declaration that: “To ensure the accountability指导留学作业提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 of local government authorities, people in particular local government areas shall, as far as practicable, be afforded the opportunity to participate effectively in their governance” Article 240[2][e]. Indeed, the democratic intention in the decentralisation provisions is made clear in the Constitution which states that: “The State shall take appropriate measures to make democracy a reality by decentralizing the administrative and financial machinery of government to the regions and districts and by affording all possible opportunities to the people to participate in decision-making at every level of national life and in government” (Article 35[6][d]).#p#分页标题#e# Such obvious democratic objective is somewhat undermined however, by the maintenance of powers of appointment by the President, including that of the District Chief Executive (Article 243[1]). Therefore, it is clear both in the provisions of the Local Government Act and the Decentralisation Policy that decentralisation in Ghana was planned to facilitate good local governance (for instance, participation and accountability are unambiguously stated). This in turn would promote local development through infrastructure development and efficient service delivery. One of the important prerequisites to achieve the aims and objectives of the democratic local governance system is electoral participation which affords the local populace the opportunity to least hold their elected public officials accountable periodically. 1.3 STATEMENT OF THE RESEARCH PROBLEM The rhetoric of decentralisation in Ghana does not match the results on the ground. Lack of adequate funding to the district assemblies and visible reluctance to devolve essential functions to the district assemblies are some of the indicators. In addition, the government still manifests overt tendencies of centralization reminiscent of the District Assemblies’ affairs through the appointment by the President of the Republic of Ghana the District Chief Executives of the District, Municipal and the Metropolitan Assemblies and thirty percent (30%) members of the Assemblies. The district assemblies are now dominated by government appointees and officials who are not directly accountable to it and which it has neither the mandate nor the influence to hire or fire let alone discipline. Matters are exacerbated by the fact that the Assemblies have failed to promote good local governance and therefore jeopardized any opportunities of poverty reduction. Though both the constitution and the Local Government Act placed emphasis on participation and accountability (both vertical and horizontal), there is no real participation at the grassroots, instead a top-down approach in different guise is in operation; again there is lack of accountability at both local and district levels. Local and district elites have usurped the decentralisation initiatives to their advantage. ‘A government has not decentralized unless the country contains autonomous elected sub-national governments capable of taking binding decisions in… some policy areas’ (World Bank, 1999: 108). But before the sub-national governments can attain a considerable level of autonomy the citizens must participate actively in the affairs of the sub-national governments. The crisis of participation facing developing countries including Ghana is leading to threats to the general stability of these countries which have only recently, in the last two decades, moved toward more democratic governance. Dahl (1956) cited in (Ifiok, 2007:8) argues that an efficient democracy is only possible when citizens can participate in governance. One of the most significant trends in Ghana’s local government politics for the past two decades has been the low level of the proportion of the eligible electorate who actually vote in the district assembly elections. Ghana’s District Assemblies and Unit committees composed of seventy (70%) elected representatives from all the communities within the districts known as the ‘Electoral Areas or wards’ which is based on the principle of universal adult suffrage, secret ballot as well as the first-past-the-post system and thirty (30%) government appointees which is done by the sitting president in consultation with traditional leaders and other interest groups within the districts. For an ordinary citizen to be elected he or she must be a citizen of Ghana, 18 years old, ordinarily a resident in the district and had paid up all his or her taxes and rates. According to the 1992 constitution: “A candidate seeking election to a District Assembly or any lower local government unit shall present himself to the electorate as an individual, and shall not use any symbol associated with any political party. A political party shall not endorse, sponsor, offer a platform to or in any way campaign for or against a candidate seeking election to a District Assembly or any lower local government unit” (Ghana, 1992:153). This particular provision has been a subject of debate among stakeholders in Ghana. Some experts argue that since there was no constitution in 1988 when the local government reform began its electoral principles could not have been based on partisanship. However, others are arguing that there is the need to amend the constitution to make the district level-election partisan since the current provision is inconsistent with the ideals of multiparty democracy being practised at the national level.#p#分页标题#e# Most often than not, some people argue that even in the most advanced democracies and industrialised countries such as USA and United Kingdom have a record of low rates of participation in local elections and so if turnout in local elections in Ghana is low what is the big deal about that? However, sight should not be lost on the fact that these countries’ democracies are well matured and they can also boast of well structured state institutions with a very good track record of performance. On the flip side, Ghana has a very young and fragile democracy which is just two decades old. Besides that, Ghana is situated within a continent where electoral disputes and political conflicts have been the conspicuous causes of most of the violent conflicts that had been witnessed in the African continent over the past two decades. Therefore, the voter指导留学作业提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 apathy which characterises the District Assembly elections should be a matter of concern to all well meaning Ghanaians as well as all well wishers of Ghana’s democratic local governance dispensation which was supposed to be the bedrock of the overall national politics. While voter turnouts of the District Assembly elections have been markedly poor across all of the districts in Ghana, the participation rates in some of the districts are even lower. There are districts where only a few percentage of the electorate turn out, whereas in other districts most electorate participate. These differences do not seem to be purely coincidental. Figure 1 below shows the national average voter turnouts of District Assembly elections in Ghana since its inception in 1988/89 to 2006 when the last election was held in percentage terms.  There were thirteen districts in the Brong Ahafo region during the 1998 and 2002 district level elections. In the two elections, only Asutifi district recorded turnout figures which were above fifty percent. Apart from the Asutifi district, none of the twelve districts in the region was able to obtain turnout figures of fifty percent or more in the two successive elections. Also, with the exception of Dormaa district which recorded 47 percent turnout value in the 2002 district level elections which was higher than the 1998 value of 44 percent, the turnout values of the rest of the districts decreased significantly in the 2002 district level elections  Figure 3 above shows the voter turnout in the 2006 District Assembly elections in Brong Ahafo region. In the 2006 district level elections, the number of districts in the region increased by six (6) districts to bring the total to nineteen districts. The average turnout in the region was (45%) which was above the national average turnout of (36%). Sunyani municipal assembly which is also the regional capital of the Brong Ahafo region recorded the lowest turnout of (31%), while two districts, Asutifi and Kitampo North both recorded (58%) which was the highest turnout in the region. #p#分页标题#e# The right to vote is one of the most essential and exquisite parts of democracy. However in local elections, about more than half of all residents fail to participate. Given that most of the elected officials in the nation are elected locally and that several of the most significant public policies are executed at the local level, this lack of participation raises serious concerns. The general consensus is that if Ghana’s current democratic dispensation which has earned the applause of the rest of the world can be consolidated, then the local governance which is supposed to be the training grounds for national leaders should be given much attention and support. For example, in 2006 District Assemblies elections, Ghana News Agency (GNA) reported that, in Accra, the national capital, “Voting in Tuesday’s District Level Elections went on smoothly but the electorate exhibited apathy towards the poll as many residents have failed to participate in the polls, which opened at 0700 hours” (GNA, 26/09/2006). Also, on July 26, 2002 in a press briefing on the District Assembly Elections observers’ report, the Associate Executive Director of Centre for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) - Dr Baffour Agyeman-Duah identifies very low and poorly managed voter education as responsible for the low turnout recorded in some parts of the country and therefore, recommends a decentralized voter education. Again, Mr Michael Boadu, Tema Municipal Electoral Officer in an interview with the GNA at Tema, expressed concern about the low turnout of the District Assembly elections and attributed it to the inability of the people to appreciate the importance of Local Government elections. (GNA, 2006). Base on some of the worries which have been expressed by most Ghanaians, I am therefore, interested in finding out the underlying factors that influence voter turnout in the District Assembly elections. My motivation of this study is based on the fact that while elections lie at the heart of political life, voting is the most important interactive political act of the electoral process. And voter turnout is key pointer of democratic responsiveness and citizen participation. Higher turnout provides greater legitimacy to elected officials; Lower turnout means指导留学作业提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041 unequal participation; and unequal participation leads to unequal influence in shaping policy priorities by elected officials. 1.4 RESEARCH QUESTIONS Perhaps, one of the most important strides to be taken in a research study is the definition of research questions. This is based on the fact that it has a great deal of impact in terms of the direction of the research process. . This study will be considered along the lines of the following basic questions. What factors account for the low voter turnout in the District Assemblies? What makes some districts achieve high turnout but others low turnout? To what extend does the level of education impact on the voter turnout? Does the level of development of the District Assemblies influence voter participation in the District Assembly elections?#p#分页标题#e# Does the level of media exposure of the District Assembly elections affect turnout? 1.5 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY In the context of what has been discussed above the fundamental objectives of this research will be to: Examine the impact of decentralisation reforms in the promotion of democratic local governance Ghana Examine the factors that explain voter turnout in the District Assembly elections. Provide suggestions on what can be done to improve the electoral participation of the decentralisation reforms in Ghana. 1.6 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY

Decentralization has the potential to improve the accountability of government and lead to a more efficient provision of public services. However, accountability requires broad groups of people to participate in local government. Also, as in all democracies, regular elections are held to give society control over governments and the policies they make. Political theorists every now and then advocate the strengthening of citizens’ participation in politics, on the justification that it serve as an engine for the cultivation of social solidarity and civic virtue. There are basically two forms of political participation- institutional and non-institutional participation. The institutional political participation denotes simply venues for participation that are provided, regulated, and sometimes even supported by the state. These vary from voting to campaigning, fund-raising, and participation in various forms of decision-making. Non-institutional participation on the other hand, comprises demonstrating, leafleting, petition writing, etc. Elections are the defining feature of representative democracy. They serve as the basic instrument for ensuring that governments are responsive and accountable to their citizens through offering the sanction of dismissal. Elections embody the democratic principle of political equality: every eligible citizen has the right to vote and every vote counts equally Therefore, voting in elections at every level of the political system is an imperative component of government accountability. “Governments should be responsive to citizens as a result of their participation, through elections, pressure, public deliberation, petitioning, or other conduits. For these forms of participation to democratically function, all potentially affected by the decisions of a government should have the opportunity to influence those decisions, in proportion to their stake in the outcome. From a normative perspective, governments are in democratic deficit when political arrangements fail the expectation that participation should elicit government responsiveness. From an empirical perspective, governments are in democratic deficit when their citizens come to believe that they cannot use their participatory opportunities and resources to achieve responsiveness. From a functional perspective, governments are in democratic deficit when they are unable to generate the legitimacy from democratic sources they need to govern” (Warren, 1996, 17).#p#分页标题#e# Ideally, citizens should be able to focus their lowest cost resource – voting – on choosing representatives who will fight most of their battles and protect most of their interests. They may join associations that fight other battles. In both cases, citizens judge whether their interests align closely enough with their representatives – whether formally elected or informally selected – that they can trust them as political Proxies (Warren, 1996, 2000). Electoral participation is widely believed to be an important indicator of the health and vitality of democracy. And statistics on voter turnout, the extent to which those entitled to vote do so, are often used to shed light on how representative governments are of the electorate. It has been argued that a healthy democracy needs citizens who care, are willing to take part, and are capable of helping to shape the common agenda of a society. And so participation - whether through the institutions of civil society, political parties, or the act of voting - is seen as important to a stable democracy. There is a widespread belief that participation in political life is good for the workings of democracy and so low turnout might represent a weak democratic system. The beauty of liberal democracy is that it is the only egalitarian system in which all the eligible citizens are given an equal right of one vote to participate in the political system; irrespective of one’s background and status in society. Morris P. Fiorina, an American political scientist describes “democratic voting as the fundamental political act”. A defining feature of any democratic system is that decision-makers are under the “effective popular control of the people they are meant to govern ” (Mayo, 1960: 60). There are serious implications if voter turnout is low in any established democracy. The main repercussion is that the leaders elected and the interests they stand for are determined by a few numbers of people in the political community. System legitimacy becomes shaky, uncertain and 指导留学作业提供指导Essay,指导Assignment,请联系QQ:949925041necessarily doubtful if few people vote. Understanding the driving forces behind what appears to be a persistent low voter turnout in the district assembly elections is of obvious importance. I must explicitly say that I am not the first person to conduct research on Local Government in Ghana. Although significant research studies have been done on decentralization and local governance in Ghana, very little literature exists on the elections of local level officials, and there is virtually no literature on the voter turnout in the local level elections. Therefore, a study like mine may provide us with the needed facts to enable us to ascertain the underlying factors behind the voter apathy which had characterised the district assembly elections since its inception in1988 to the last elections in 2006 in order to appreciate the dynamics of electoral participation in decentralization and democratic local governance in Ghana. #p#分页标题#e# To policy analysts, administrators, academia and the advocates of democratic local governance for achieving good governance and, even government officials, the findings of this research should serve as a useful guide and further research work. Scope of the Study The study focuses on the factors affecting voter turnout in the District Assembly elections. One of the disturbing aspects of local government and decentralization in Ghana, since its inception in 1988 has been poor electoral patronage. In Ghana, decentralization, devolution of power to representative local government units was expected to improve popular participation, transparency, empowerment and responsiveness. Therefore, the overwhelming enthusiasm for decentralization was centred on accountability of elected local leaders to the people. It is therefore, imperative to look at the whole concept of decentralization programme in Ghana again and make the reviews that can encourage the citizens to participate actively in their District Assemblies’ programmes which begin with the elections of the people’s representatives to take key decisions on their behalves. 1.7 ORGANIZATION OF THE STUDY The study spreads over six chapters. Chapter One: Introduction to the Study. This Chapter deals, inter-alia with the background of the study which is a short description of the country Ghana, brief overview of decentralization in Ghana dating back from British colonial rule through to the PNDC government’s decentralization programme in 1988, rationale for decentralization in Ghana, statement of the research problem in the area of poor patronage in the local level elections, research questions concerning the determinants of voter turnout in the local level elections, objectives of the study, significant of the study and organization of the study. Chapter Two: Conceptual Framework. This Chapter provides the study with a theoretical and conceptual framework to create a deeper understanding of the conceptual and theoretical dimensions within which decentralisation and democratic local governance are discussed. The chapter also investigates the determinants of voter turnout in the context of voter turnout theories, the main instrument of analysis of this study. Chapter Three: Methodology of the study. It outlines and justifies the use of quantitative approach as an appropriate method for data collection in this study as well as some of the problems encountered during the data collection process. Chapter Four: The historical perspective of local government reforms in Ghana from independence up to the last military regime of the PNDC government in the 1980s are delved into. The chapter then deals with the new decentralization and local government system popularly known as the District Assembly system which is clearly stated in chapter twenty of the 1992 constitution of the Republic of Ghana. This Chapter also provides a general profile of the institutional arrangements for local governance as well as the functions of various local governance structures in the#p#分页标题#e# District Assembly system. Chapter Five: Analysis and Findings. This Chapter uses district-level data for empirical analysis of the District Assembly elections in Brong Ahafo region. In this direction cross tabulation and basic regression analyses method are used to analyse the quantitative data collected. Chapter Six: Conclusion and Recommendations. This Chapter recaps the findings and some emerging ideas in the inquiry. It draws conclusions and suggestions for improvement. In addition, the Chapter provides areas for further research. CHAPTER TWO: CONCEPTUAL AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK INTRODUCTION This chapter sets out to shed light on the concept of decentralization and democratic local governance and the ideals of local government. In this context, the features of decentralization and democratic local government shall be explicated. Secondly, the theory of voter turnout which is the main focus of this study shall be vigorously pursued. The significant of theory of voter turnout in this study is that, it will be the instrument of analysing the extent to which the policy objective of grass-root political participation of the decentralization programme has been realised in practice since its inception in 1988. THE CONCEPT OF DECENTRALIZATION AND DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE. The concept of decentralization in a sense has been used generally to encompass geographical, functional and organizational forms in the diffused of power. The practice of decentralisation raises questions not simply of local management, but in the broader perspective, also of local governance. Decentralisation, as a part of local governance, helps to move thinking away from state-centred perspectives to incorporate elements which are frequently considered to be outside the public policy process. Most definitions of decentralization had been traditionally drawn from the Public Administration and Economic Development literature. For instance, Smith (1985, pp.1) defines it as “The delegation of power to lower levels in a territorial hierarchy, whether the hierarchy is one of governments within a state or offices within a large-scale organization”. ‘A government has not decentralized unless the country contains autonomous elected sub national governments capable of taking binding decisions in… some policy areas’ (World Bank, 1999: 108). According to Rondinelli, et al. (1983), decentralization is “The transfer of planning, decision-making or administrative authority from the Central Government to its field organizations, local administrative units, semi-autonomous and parastatal organizations”. These definitions embrace four major dimensions namely: deconcentration, delegation, devolution and privatization to non-governmental institutions normally identify by most decentralization literature. Deconcentration is the system whereby administrative responsibilities from central ministries and departments are shifted to regional and local administrative levels by setting up field offices of national departments and relocating some authority for decision making to regional field staff;#p#分页标题#e# Delegation is a process by which national governments pass on management authority for specific functions to semi-autonomous or parastatal organizations and state enterprises, regional planning and area development agencies, and multi- and single-purpose public authorities; Devolution is a policy which seeks to strengthen local governments by giving way to them the authority, responsibility, and resources to offer services and infrastructure, protect public health and safety, and formulate and implement local policies; Privatization is the switch from state-planned to market economies purposefully for strengthening the private sector, privatizing or liquidating state and governance enterprises, downsizing large central government bureaucracies, and strengthening local governments; (Cheema and Rondinelli,2007:ch1pp.2-3). Decentralization goes beyond just the transfer of power, authority, and responsibility within government, but it also includes the sharing of authority and resources for determining public policy within society. In this growing concept The Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.orgof governance, decentralization practices can be branded into about four forms: political, fiscal, administrative, and economic. Political decentralization includes “organizations and procedures for increasing citizen participation in selecting political representatives and in making public policy; changes in the structure of the government through devolution of powers and authority to local units of government; power-sharing institutions within the state through federalism, constitutional federations, or autonomous regions; and institutions and procedures allowing freedom of association and participation of civil society organizations in public decision making, in providing socially beneficial services, and in mobilizing social and financial resources to influence political decision making”. (Cheema and Rondinelli, 2007:ch. 1pp. 7). Fiscal decentralization includes “the means and mechanisms for fiscal cooperation in sharing public revenues among all levels of government; for fiscal delegation in public revenue raising and expenditure allocation; and for fiscal autonomy for state, regional, or local governments” (Cheema and Rondinelli, 2007:ch. 1pp. 7). Administrative decentralization includes “deconcentration of central government structures and bureaucracies, delegation of central government authority and responsibility to semi-autonomous agents of the state, and decentralized cooperation of government agencies performing similar functions through “twinning” arrangements across national borders” (Cheema and Rondinelli, 2007:ch. 1pp. 7). Economic decentralization includes “market liberalization, deregulation, privatization of state enterprises, and public-private partnerships” (Cheema and Rondinelli, 2007:ch. 1pp. 7). The importance question is how does decentralization relate to democracy? Democracy guarantees individual freedom, gives all citizens equality before the law and allows them to elect and remove their political leaders. The fundamental assumption of democracy as a form of governance rests on its etymology as rule by the whole populace rather than by any aristocrat, monarch, philosopher, bureaucrat, expert, or religious leader (Shapiro 1999: 29-30 & 23).#p#分页标题#e# According to (Oxford English Dictionary, 1933), democracy is "government by the people; that form of government in which the sovereign power resides in the people as a whole, and is exercised either directly by them. . . or by officers elected by them." It is the only system in which all the citizens are given an equal opportunity to participate in the political system irrespective of one’s background and status in society. Democracy provides an institutional framework for participation by all citizens in economic and political processes. The link between the two is so close that they are frequently used together by many scholars. There is a debate among scholars with regards to the nature of the relationship between decentralization and democracy. Some see democracy as a prerequisite for decentralization, but others think otherwise. The strongest theoretical evidence pointing towards the existence of a relationship between democracy and decentralization comes from Alexis de Tocqueville in his study of the United States at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Along with Max Weber, Tocqueville was one of the first theorists to talk about the relationship between decentralization and democracy. Both of them base many of their arguments on the assumption that within modern states, bureaucracies tend to centralize. But while Weber’s submission for limiting the over-centralization of bureaucracy within a state is by strengthening parliament and creating a multiple set of bureaucratic structures that limit each other’s actions, the suggestion of Tocqueville points more toward the creation of a system of government within which local government is given a major role. In one way or the other, both democratic governance and decentralized government have been adopted by many countries over the past two or three decades. At the end of the 1990s, about 95 percent of the countries with democratic political systems had also sub-national units of government or administration. The center for Democracy and Governance of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has also written extensively on the concept of decentralization and democratic governance. It defines and explains the two distinct concepts as follows; (1) Decentralization is a process of transferring power to popularly elected local governments. In order to have significant autonomy decentralization requires the existence of elected local governments who are answerable to their constituents. This definition is more of political decentralization. Like Cheema and Rondinelli, USAID also identifies three types of decentralization namely: Devolution is “An increased reliance upon sub-national levels of governments, with some degree of political autonomy, that are substantially outside the direct central government control yet subject to general policies and laws, such as those regarding civil rights and rule of law”. Deconcentration is “The transfer of power to an administrative unit of the central government, usually a field or regional office. With deconcentration, local officials are not elected”.#p#分页标题#e# Delegation is “The transfer of managerial responsibility for a specifically defined function outside the usual central government structure” (USAID, 2000:6). Apart from the above three types of decentralization, It again talks about the three dimensions of decentralization and considers them to be the key constituents of power. They are; political, financial and administrative dimensions. The political dimension is referred to as political decentralisation. It involves the transfer of political authority to the local level through the establishment or reestablishment ofThe Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org elected local government, electoral reform, political party reform, authorization of participatory processes, and other reforms. The financial or fiscal decentralization on the other hand, refers to the transfer of financial power to the local level. It entails the removal of all bottlenecks that inhibit inter-governmental transfer of resources as well as giving local levels greater authority to generate their own resources. The administrative dimension is often referred to as ‘administrative decentralisation’. It involves the full or partial transfer of an array of functional responsibilities to the local level, such as public health, the operation of schools, the management of service personnel, the building and maintenance of minor and feeder roads, and garbage collection. The responsibilities vary by country and by the type of local authority (USAID, 2000:6). (2) The concept of governance is defined by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) as the exercise of economic, political and administrative authority to manage a country’s affairs at all levels. It comprises mechanisms, processes, and institutions through which citizens and groups articulate their interests, exercise their legal rights, meet their legal obligations and mediate their differences. Local governance is therefore, “Governing at the local level viewed broadly to include not only the machinery of government, but also the community at-large and its interaction with local authorities”. (3) Democratic local governance is therefore, “A local governance carried out in a responsive, participatory, accountable, and increasingly effective (i.e., democratic) fashion” (USAID, 2000:7). Even though, both USAID and Cheema and Rondinelli use different paths in discussing the concept of decentralization, they arrive at the same destination in terms of their substance. THEORY OF VOTER TURNOUT In an ideal scenario, at the heart of effective decentralization and democratic local governance are regular local elections or electoral accountability. When there are persistent elections at the local level which citizens voluntarily participate massively then, local leaders would eventually become conscious that they might stand the risk of sacrificing their political careers if they dismiss or ignore the community consensus (USAID, 2004). Election is about the allocation of power, power to take future decisions that affect the welfare of the society. It is the basis of legitimacy. Electoral participation at the local level gives the local political system legitimacy before any other form of participation can follow. #p#分页标题#e# Using aggregate level data from official sources covering the whole Brong Ahafo region, this study investigates the determinants of voting turnout at the local level elections in Ghana. There is a considerable literature on how and why people vote in elections. Several Studies have used diverse approaches to explain voter turnout. In the comparative literature on electoral turnout a myriad of factors which are believed to explain the differences in people’s participation in elections are found. Following André Blais & AGNIESZKA Dobrzynska (1998:239-261), Kuenzi, M., & Lambright, G. (2007:265-690) and other relevant literature on voter turnout the dominant approaches emphasize socio-economic resources, politcal institutions and politics as well as the political and cultural background as the most important determinants of voter turnout. Although I am not analyzing electoral participation at the individual level but instead focusing on turnout levels in the districts, some of the macro-variables used utilize the arguments put forward by studies at the individual level. Global Studies of Electoral Turnout André Blais & Agnieszka Dobrzynska conducted study on voter turnout in 324 democratic national lower house elections held in 91 countries between 1972 and 1995. Based on their study they distinguished between three blocs of factors that affect turnout namely: (1) socio-economic environment; (2) institutional variables; and (3) party systems. They formulated certain propositions to explain voter turnout variations. These propositions focused on factors such as economic development; degree of illiteracy; population size and density; the presence or absence of compulsory voting; voting age; the electoral system; the closeness of the electoral outcome (competition); and the number of parties. The eight independent variables of Blais & Dobrzynska are explained below with the following sub-themes: Hypothesis and operationalisation. Socio-Economic Environment Economic Development. Hypothesis 1: A considerable level of economic development fosters voter turnout. Argument and operationalisation of economic development: The existing literature (Powell, 1982) suggests that economic development can have major effects on the political involvement of citizens. Economic development promotes the creation and dissemination of socio-economic resources such as access to information and higher education levels and income. Furthermore, economic development transforms the relations among different groups in society, thereby creating a diversity of interests. All of this may well amplify the political involvement of citizens and stimulate voter turnout. In their model, they included the usual indicator of economic development, gross national product per capita. They concluded in their findings that higher economic growth does not foster turnout, so the most important issue that appears to matter is the economic structure and not the economic conjuncture (243).#p#分页标题#e# The Rate of Literacy: Hypothesis 2: High levels of illiteracy tend to inhibit voter turnout. Argument and operationalisation of levels of literacy: They argued that it is not only the economic development that matter since at a given level of economic development, turnout is affected by the degree of literacy. A minimum degree of literacy is almost a prerequisite to a good turnout. Their finding affirms of the fact that low levels of literacy can reduce turnout. Therefore, they concluded that it is extremely difficult to achieve a higher turnout when there is a high degree of illiteracy (244). Size and Population Density: Hypothesis 3: Voter turnout tends to be higher in small and densely populated countries. Argument and operationalisation of size and population density: They support the view that smaller countries are able to arouse a greater sense of community which in itself fosters turnout. The indication is that the important difference is between smaller countries and all other countries. Their results indicate that turnout is somewhat higher in small and also more densely populated countries. Institutional Setting

Compulsory Voting: Hypothesis 4: There are high levels of voter turnout in countries with compulsory voting. Argument and operationalisation of compulsory voting: The most important variable is legislation imposing compulsory voting. Its influence has been seen in all the studies analyzing the effects of institutional factors on turnout. However, turnout seems not to be affected by the obligation to vote when there are no penalties for failure to comply. They argued that compulsoryThe Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org voting does not really have any impact unless penalties are set for electors who decide to abstain. A merely symbolic obligation is not sufficient. They found out that all other things being equal, turnout as a function of the number of registered electors is higher in countries where voting is compulsory and penalties are imposed for failure to comply. Voting Age: Hypothesis 5: The lower the voting age, the lower the turnout Argument and operationalisation of voting age: They argue that younger electors have lower propensity to vote due to lack of political experience. Therefore if the voter age is reduced from 21 years to 18 years then, it will decrease the turnout. They found turnout to be slightly higher in countries with voting age at 21 years. Electoral system(Proportional Representation): Hypothesis 6: On the electoral system, the standard assumption is that turnout tends to be higher in proportional representation systems with fewer parties. Argument and operationalisation of proportional representation (PR) system: It was argued that PR election with low vote threshold and large district magnitudes, such as the party list system, enhance the chances for smaller parties with scattered support to go into parliament with only a modest share of the vote, and therefore this could increase the motivation of their supporters to partake in the election. The results concerning the electoral systems explained that turnout is slightly higher in proportional representation (PR) systems than in plurality, majority or mixed systems.#p#分页标题#e# Party Systems Electoral Competition(Closeness of elections) : Hypothesis 7: The higher the level of electoral competition the higher the voter turnout. Argument and operationalisation of closeness or electoral competition: The measure of closeness is the gap (in vote shares) between the leading and the second parties. They considered closeness to matter. When there is a gap of 10 points between the leading and the second parties, turnout is reduced by 1.4 points. It should be stressed that they are measuring only the impact of overall systemic competitiveness. They argued that election may be very close at the national level but not close at all in a number of districts. Those results thus underestimate the true impact of closeness. Number of Political Parties: Hypothesis 8: Turnout tends to be lower in countries with so many number of political parties. Argument and operationalisation of number of political parties: Even though they considered multi-party system to offer more choices to electors which can boost turnout, they however, argued that the greater the number of parties, the more complex the system, and the more difficult it can be for electors to make up their minds. Moreover, the greater the number of parties, the less likely it is that there will be a one-party majority government. (Jackman 1986) considers elections that produce coalition governments as being less decisive since the government there after the elections is a product of backroom deals among the parties rather than the electoral outcome per se. Their findings on the number of parties confirmed Jackman’s finding that turnout tends to be reduced when the number of parties increases. Turnout declines by 4 points when the number of parties moves from 2 to 6, but by only 2 points from 6 parties to 10 and from 10 to 15. Studies of Electoral Turnout in Africa. Another study in 2007 by Michelle Kuenzi and Gina M.S. Lambright also sought to examine the factors that influence voter turnout in sub-Saharan Africa’s multiparty regimes that have had two consecutive elections since the democratic transitions in the 1990s. The strategy adopted by the two authors was to review most of the significant research findings on voter turnout in other parts of the world before they selected from among these factors they considered applicable to Africa’s context. They therefore used an “eclectic approach” to scrutinize the influence of variables associated with several theoretical approaches on turnout. To this end, using aggregate-level data, they studied the influence of the following categories of variables on turnout in Africa at the cross-national level. Institutional variables include; concurrency of presidential and legislative elections, type of electoral formula, bicameralism, presidentialism, and multipartism. Contextual variables include; the level of democracy, media exposure, and electoral experience. Socio-economic context include; urban population, GDP per capita, and annual growth rates.#p#分页标题#e# The authors identified the under-mentioned variables as the most significant explanatory factors that influence electoral turnout in legislative elections in Africa and therefore, made the following claims: Africa Countries with concurrency of presidential and legislative elections experience higher voter turnout.

Potential voters perceive presidential elections as more important than legislative elections and therefore more inclined to vote in presidential elections. And also given the costs associated with voting, particularly in rural Africa, where voters may have to travel some distance to reach a polling station. Holding presidential and legislative elections concurrently is therefore likely to boost turnout in legislative elections through the positive ripple effect of presidential elections. Unicameral systems elicit higher turnout rates. Bicameralism diffuses legislative power. The limited influence of bicameralism on turnout may be a result of the weak nature of bicameralism in Africa. According to Lijphart (1999) cited in Kuenzi & Lambright (2007:679), the power of the legislative bodies in Africa’s bicameral legislatures tends to be unbalanced. Often the members of the second chamber are not directly elected and may comprise traditional chiefs or the ruling party’s gurus. In Africa, voter turnout is consistently higher when elections are conducted using proportional electoral rules. Their argument on this proposition is based on (Jackman, 1987:408) assertion that for smaller parties to attain any meaningful legislative representation in highly disproportional systems, there is the need for them to amass a considerable number of votes, but which is difficult for them. This therefore reduces the reward of voting for the minor-parties’ supporters. There is more likely for the votes of minor-parties’ supporters to be wasted in greater disproportionality systems. Disproportionality appears to be a major disincentive to potential minor-party voters to cast a ballot. It appears that electors are more inclined to vote when the voting system seems fairer for all parties, including small ones implying voters are more likely to find amenable parties. Voter turnout is higher in countries with greater electoral experience in Africa. Electoral experience is measured as the number of elections held in each country since the reintroduction of multiparty elections up to the election included in their study. There is anticipation that people need a little experience with new institutions before their behaviour is consistent with the incentives provided. The Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.orgPeople are also likely to acquire the habit of voting as they gain more and more experience with democracy. Media exposure has a strong positive effect on turnout in Africa. Media exposure is measured as the number of radios per capita. People with regular access to radios are likely to be knowledgeable about the electoral campaigns. They are also likely to be more informed about the timing and logistics of the election, where and when to vote. The reason why the number of radios has such a powerful effect is that it captures both the media access and level of development.#p#分页标题#e# Voter turnout is lower where populations are more urbanized. Most ruling parties in Africa often receive a considerable support from rural areas and therefore concentrate their mobilization efforts outside the urban areas. In most African countries political parties are easily able to mobilize voters in rural areas where the threat of sanctions for not voting may be somewhat effective and also endemic poverty exacerbates the impact of party efforts to buy votes. Western Studies of Electoral Turnout. Local and regional disparity in electoral participation is also a familiar phenomenon in many western countries. Scholars of turnout levels have more often relied on political models and variables to explain these differences. In a study of electoral turnout, Andreas Ladner looked at what explains electoral turnout in Swiss municipalities. In this study, three main propositions of socio-economic and socio-demographic variables, cultural and political background variables and political institutions and politics were examined. These propositions focused on factors such as education, age, wealth, limited performance, problems, size, local parties, local parties influence, influence of associations, catholics, French, Italian, parliament, Assembly voting, proportional representation (PR), fragmentation, polarization and competitiveness.

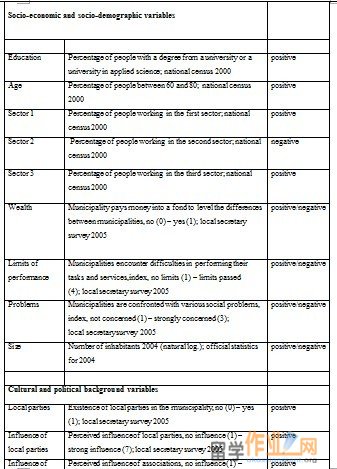

Some of the variables discussed are more generally related to the citizens’ propensity to participate in politics, while others are more directly related to local politics. Below, it is suggested how the explanatory factors accentuated by these studies may be applied to the Ghana setting.

DEPENDENT VARIABLE The dependent variable is voter turnout measured as a percentage of the total number of registered voters who cast a ballot including the rejected ones in the District Assembly elections since that is a measure that is reported in official documents. As compared with the electoral turnouts in the local elections in some West African countries available on the internet as shown in table 4 below, turnout of (50%) and above in any district may be considered high while those with turnout below (50%) may be considered low. FIGURE 5: VOTER TURNOUT IN LOCAL ELECTIONS IN SIX WEST AFRICAN COUNTRIES.

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES Like their study of regional variations of electoral participation in Bangladesh, Baldersheim, Jamil and Aminuzzaman (2001:55), used the modernization theory published by Seymour Martin Lipset in 1959 in his article, ‘SomeThe Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy’ which claims that some level of socio-economic modernization are prerequisite for democratization. Therefore, the independent variables of this study are categorised into two main sets; (1) modernization factors and (2) political factors.#p#分页标题#e# Modernization Factors: The adult literacy rate of the district. The adult literacy rate is measured as percentage of adult population in a particular district who can read and write in both the English language and the dominant local language in that district. This is because the English language is both the official and national language in Ghana. It is a language of instruction from primary four (4) up to the tertiary level and also, one of the compulsory examinable subjects a person must pass in order to progress from the lower stage to the higher level of the educational ladder. It is a language for government business. On the other hand, in order to encourage more local participation in the business of the District Assemblies, the Assemblies by their standing orders are allowed to conduct their business including their sittings in the dominant local language of the districts. The campaign platform mounted officially by the Electoral Commission of Ghana for the candidates to sell their policies to the electorate is conducted in the local language predominant in the districts since majority of the adult population can speak and understand the local language well. Below are the official local languages which are usually used for national transactions within the country aside from the English language: Government-Sponsored Languages 1. AKAN (Ashanti, Fante, Akuapem, Akyem, Kwahu) (Written Twi) 2. DAGAARE / WAALE Spoken in Upper Western Region (UWR) 3. DANGBE Spoken in Greater Accra. (G/A) 4. DAGBANE Spoken in Northern Region (NR) 5. EWE spoken in Volta Region (VR) 6. GA spoken in Greater Accra Region (G/A) 7. GONJA spoken in Northern Region (NR) 8. KASEM spoken in Upper Eastern Region (UER) 9. NZEMA spoken in Western Region (WR The 2000 Ghana’s Population and Housing Census defines literacy in Ghana as “The ability to read and write simple statements in any language, with understanding and relates to those aged 15 years and older”. The effective literacy rate for Brong Ahafo region is (49%), which is lower than the national average of (55%). The implication is that information flow in the forms of posters, brochures, and written advertisements will seriously be hindered because of the low literacy level. Verba, Schlozman and Bardy (1995) cited in Blais & Dobrzynska (1998:242) consider voting to be the least demanding form of political activity which does not require any considerable civic skills. Yet, some minimum degree of skill may be needed and they acknowledge that people with insufficient skill are less likely to vote. This reasonably presupposes that high levels of illiteracy may tend to lower turnout. Hypothesis 1: The higher the adult literacy level of a district, the higher the voter turnout.#p#分页标题#e# The wealth of the districts There is sound indication that economic growth (GNP per capita) drives political change in democratic directions. An essential mediating factor is the improvement of the quality of life for a broad spectrum of the inhabitants that goes along with economic growth. These diverse indicators of socio-economic modernisation have been revealed to drive democratisation across nations. The main indices of wealth used by Baldersheim, Jamil and Aminuzzaman in their study of electoral participation in Bangladesh were percentage of households with electricity, sanitary toilets, and running water facilities since households with such facilities are said to be well to do in Bangladesh. Akin to Ghana wealth is measured by the percentage of households with the following facilities; access to electricity, access to improved and safe drinking water source, safe sanitation, improved waste disposal and access to health care. Households with such facilities in the districts may be said to better-off households and as such those districts are considered to be economically developed. Because of financial constraints, state institutions are not able to conduct extensive research on income levels in Ghana, so normal poverty levels based on estimations. According to Blais and Dorbrzynska (1998:242), there is an impact of the level of economic development on voter participation and therefore, a moderate level of economic development is essential in order to obtain a high turnout which is at the national level. Political participation calls for important resources such as information, The Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.orgtime, skills, and etcetera, therefore those with high level of economic development are likely to vote more than those in under-developed communities. This is because there is assumption that poor people tend to think about how they can survive from the harsh economic conditions they find themselves and therefore, do not care about what happens in the wider community in the area of politics. However, Devas and Delay (2006:683) found voter turnout to be generally higher not only in local level elections but also in poor and low- income areas compared to well-off neighbourhoods. Two scenarios are given as possible explanations for this kind of results in the local level elections. First, the deplorable state of affairs of the citizens may impel them to take hold of any opportunity in achieving some improvement. The second scenario is related to “ ‘vote bargaining’, in which community leaders organize to bargain with electoral candidates in return for delivering blocks of votes. Though, such situation may bring some level of improvement in the communities it may eventually culminate in ‘vote buying’. Hypothesis 2: The higher the level of wealth of a district, the higher the voter turnout. The rural-urban status of the districts. The rural-urban classification of localities in Ghana is population based, with a population size of 5000 or more being urban and less than 5000 being rural as used in all the earlier censuses. The population of Ghana is predominantly rural: Only two regions; Ashanti region (51.3%) and Greater Accra region (87.7) have levels of urbanization above average. The Brong Ahafo region, (37.4) is the fourth most urbanized region in Ghana according to the 2000 Population and Housing census. Only four districts, Sunyani (73.8%), Techiman (55.7), Berekum (54.7) and Tano (43.2%), have levels of urbanization above the regional average, with Sunyani, Berekum and Techiman having much higher proportion of urban than rural population. There is a general feeling that rural dwellers are more likely to vote specifically in the local elections more than the urban dwellers. This is based on the communal lifestyle among the rural dwellers who consider themselves as one big family as compared to “each one for himself” attitude among urban dwellers. It is therefore easier to induce rural dwellers who lack certain basic social amenities with few infrastructural projects to go to the polls more than the urban folks who may never be satisfied with the local authorities due to their level of exposure to modern technologies and foreign cultures.#p#分页标题#e# (Kuenzi & Lambright, 2007:680) research findings on the individual electoral participation suggest that rural dwellers are more likely to vote than their urban residence counterparts in Africa. On the other hand, most research works on voter turnout in advanced democracies in Europe identify higher turnout in urban than rural areas. Therefore, in this study my working hypothesis concerning the urban-rural status will be; Hypothesis 3: The higher the rural status of a district, the higher the voter turnout. The level of media exposure of the programmes and the elections of the districts. The populace in most African countries generally make selective choices in media access. The lowest participation rate is in the print media, a tendency that may be related to high illiteracy rates and high printing costs. Radio is the most common form of media because most of the rural people can afford it and easily access it. To promote civic education and to involve the citizens in governance, Ghana had since the 1990s been supporting and encouraging the establishment of community radio stations in every corner of the country. In Ghana because of inconsistent supply of electricity to the public most Ghanaians rely so much on radios that use dry cells rather than electricity to listen to the news. Therefore, the level of media exposure in this study refers to the number of media houses particularly the radio (FM) stations available in each district to give general as well as electoral education to the citizens. Presently, there are more than twenty (20) radio stations spreading across the Brong Ahafo region with Sunyani, the regional capital having as high as five (5), four (4) private and one (1) state-owned radio stations. Kuenzi and Lambright (2007, p.680) find media exposure measured in terms of the number of radios per capita in a country as having a consistent significant positive effect on voter turnout in Africa. They assert that “people with regular access to radios are likely to be more knowledgeable about the electoral campaigns. They are also likely to be more informed about the timing and logistics of the elections”. In Ghana electioneering campaigns, advertisements and electoral education of the local elections are the responsibility of two state institutions, the Electoral Commission and the National Commission for Civic Education. Their work is supplemented by the local radio stations, both public and private as part of their corporate social responsibilities. Even though it is difficult to quantify the level of publicity that is given to the local election, because it is not based on partisanship where you can contact the political parties to ascertain the cost they incur on media campaign, so I used rather the number of radio stations in each district as a yardstick since that one is easily accessible. Hypothesis 6: The higher the number of radio stations per a district, the higher the voter turnout. Political Factors

(E)The population size of the districts.#p#分页标题#e# The population size of Ghana which is the total number of people living in the country is estimated at 21.8 million. The population density which is also the number of people who live on a square kilometer of land is estimated as 91.39 per sq km. (UN estimate 2005). Accra, the capital, has the highest population of 2.2 million (World Bank estimate 2002). The population of theThe Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.org Brong Ahafo region from the 2000 census is 1,815,405, accounting for 9.6 percent of the country’s total population. The size of a district is measured by the total number of people who are residing in it. District Assemblies in Ghana are either Metropolitan (population over 250,000), Municipal (one town Assemblies with population over 95,000) or District (population 75,000). The Metropolitan Assemblies have the greater share of the population follow by the Municipal Assemblies before the District Assemblies. Blais & Dobrzynska (1998:244) find voter turnout to be higher in smaller countries, because these smaller countries tend to stimulate a greater sense of community which in itself boost a higher turnout. In smaller communities people are closer to each other and are aware of what is happening in the locality and also feel part of the community. This assertion is corroborated by Baldersheim, Jamil and Aminuzzaman (2001:60) who also find turnout to be higher in smaller communities due to the fact that those communities tend to be more homogeneous. On the basis of that a high proportion of the population conforms to common set of rules, and for that matter may enhance community identity, imbue the sense of ‘we-feeling’ and so arouse interest in the fate of the community. This may further lead to interest in community politics and therefore increase voter turnout. They consider it to be easier to maintain personal contact between the electorate and the candidates in smaller units. They see personal knowledge of the candidate as a vital factor that may increase voting, especially in communities with high illiteracy rates and inadequate access to the electronic media. Hypothesis 4: The smaller the size of a district, the higher the turnout. (F) The electoral competition within the districts. Concerning the electoral competition within the districts, it refers to the total number of people who contested in each district in relation to the total number of seats they were vying for. Turnout is likely to be high if there are more parties contesting the election for the simple reasons that; (1) the voters would be given wide options to make a choice since at least they would get a party that may somewhat meet their interests and (2) the large number of parties would also boost electoral mobilization. Blais & Carty (1990) and Blais & Dobrzynska (1998) cited in Blais (2006:118) report that, turnout is low in elections that produce single-party majority government. Blais and Dobrzynska (1998:248-249) however, identify another scenario that if there are more parties it makes the elections more complex and therefore more difficult for the voters to make up their minds concerning the party to vote for since they know that it is difficult for one party to win the majority. They feel the number of parties should be 2 or 3 so that the electorate can feel that his or her vote can elect a party who forms the next government. #p#分页标题#e# Anthony Downs (1957) cited in Baldersheim, Jamil and Aminuzzaman (2001:63) suggests that a bi-partisan system with concise range of programmes is preferable to the rational voter than multi-partisan political arrangement since the former is more feasible to support electoral mobilization than the latter. Because in Ghana the District Assembly elections are non-partisan, the number of political parties is substituted with the number of people who actually contested in the local elections. Hypothesis 5: The more intense (higher) the electoral competition, the higher the electoral turnout. (G) Age of Voters in the districts.

This refers to the proportion of the population that is eligible to vote in the local elections. In general, if the percentage of the voter population is made up of the youngest electorally significant cohort, thus those from the ages of 18 to 39 years in a particular district, then that district is likely to register low turnout in the local elections. This is because unlike the national elections where stakes are high and therefore the political parties do everything within their power to woo these youngest voters who constitute about (65%-70%) of the voting population to go to the polls through such means like distribution of fiscal cash, free T’-shirts, drinks, food and other material benefits as well as promise of securing visas and good jobs for them. In Ghana, because the youth between the ages of 18 and 39 constitute the majority of voter population in Ghana, all the political parties have youth wing with national executive position in the form of ‘National Youth Organizer’ within the parties as a strategy to win more youth vote. However, in the local elections, the stakes are relatively low and most of the candidates are poor with the majority being teachers who are unable to raise personal income to attract the youth to participate in the electoral process at the local level where the election is non-partisan. The youngest voters are less likely to participate than their elders, possibly for generational reasons, but definitely for life-cycle reasons, namely; they are highly mobile, have developed less of a stake in their communities, and they have less knowledge about electoral processes, voting and candidates. In their research of electoral participation in Bangladesh, Baldersheim, Jamil and Aminuzzaman (2001:62) hypothesize based on the life-cycle argument that, “The higher the number of middle-aged voters, the greater is the level of mobilization and higher is the turnout. They consider the middle-aged voters to have more at stake and so more involved in the affairs of the community. They see middle-age people as people whose lives mainly depend on government services, because they have begun acquiring assets like houses and vehicles. They are also, people who have started giving birth to children and therefore may be looking for quality education, efficient medical services and many more for their children which depend much more on government’s policies and so they tend to show more interests and concerns in politics. #p#分页标题#e# Hypothesis 7: The higher the voter age being the youth (18-39years) in a district, the lower the voter turnout. (H) Ethnic heterogeneity of a district. Ethnicity relates to a particular race, nation, or tribe and their customs and traditions. While heterogeneity refers to different groups of relatively equal size located in the same community. Ghana’s population, which is currently estimated at about 22 million, is a huge mixture of big and small ethnic groups. The major ones are the Akan, Mole Dagbani, Ewe, Ga-Dangme, Guan, and Gurme. According to the 2000 census data, the predominant ethnic group, Akan Constituted 8, 562, 748 or (49.1%) of the population occupying five out of the ten regions in Ghana. The Akan constitutes the predominant ethnic group in the Brong Ahafo region, and in all the districts, except Sene, where the Guan constitutes the largest ethnic group. The Mole Dagbon constitutes the second largest ethnic group in the region and in all districts, except Sene and Atebubu. Even though the New Patriotic Party and the National Democratic Congress, the two dominant parties enjoy much support from Akan and Ewe ethnic groups respectively at the national level elections, there is no data or previous studies to furnish us with information on political behaviour of people belonging to different ethnic groups at the district level elections since the district level one is non-partisan. However, it has been observed that ethnicity always becomes a deciding factor about who should be elected to the various District Assemblies in the districts where ethnic heterogeneity is clear and obvious. The reasons for this state of affairs are that; (1) The different groups try to push their members to the Assemblies for social recognition of their ethnic groups since Assembly The Essay is provided by UK Assignment http://www.ukassignment.orgmembers, particularly in the rural districts are regarded as honourable and powerful members of the communities. (2) Because of nepotism and the ‘winner-takes-all’ politics in Ghana, people in highly heterogonous districts always want to get closer to the reign of power as a means to secure maximum benefits to their members and voting is the way to increase the political power of one’s group. Therefore, there is propensity for people in these districts to vote in the local level elections. According to Friday (2007: 302), ‘ethnicity is an extremely significant although not deciding factor in Ghanaian elections’. Posner (2005: 227) arrives at essentially similar results, viz. that ethnic voting really matter in rural areas, and that ‘the pattern of tribal voting (…) is more pronounced in the one-party elections than in the multi-party elections’. Hypothesis 7: The higher the ethnic heterogeneity of a district, the higher the voter turnout. CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY OF THE STUDY.